If you’ve got a dark roof, you’re spending almost $700 extra a year to keep your house cool, say SEBASTIAN PFAUTSCH and RICCARDO PAOLINI.

If you visit southern Greece or Tunisia, you might notice lots of white rooftops and white buildings to reflect the intense heat and keep residents cooler.

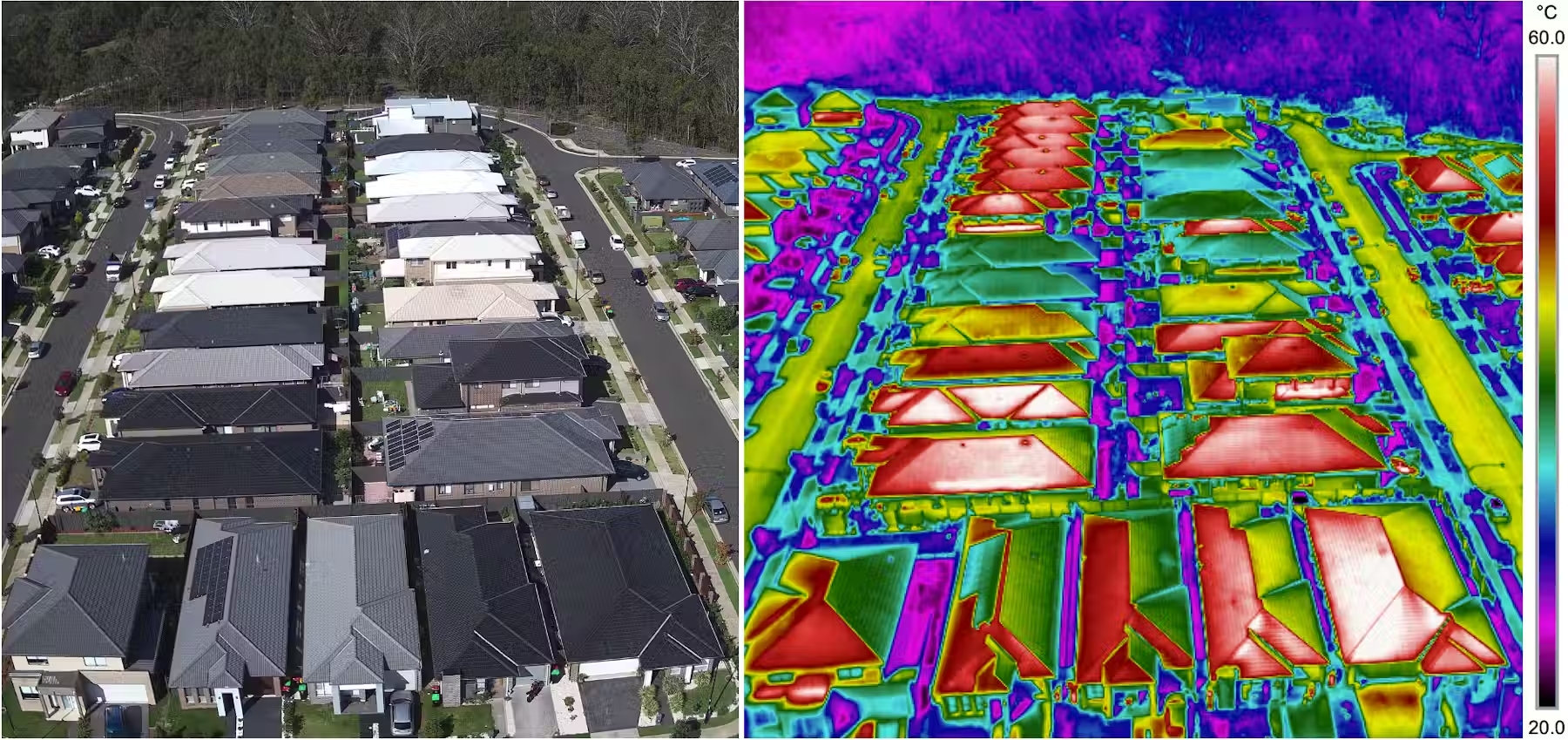

It’s very different in Australia. New housing estates in the hottest areas around Sydney and Melbourne are dominated by dark rooftops, black roads and minimal tree cover. Dark colours trap and hold heat rather than reflect it. That might be useful in winters in Tasmania, but not where heat is an issue.

A dark roof means you’ll pay considerably more to keep your house cool in summer. Last year, the average household in NSW paid $1827 in electricity. But those with a lighter-coloured cool roof can pay up to $694 less due to lower cooling electricity needs. Put another way, a dark roof in Sydney drives up your power bill by 38 per cent.

When suburbs are full of dark-coloured roofs, the whole area heats up. And up. And up. This is part of the urban heat island effect. In January 2020, Penrith in Western Sydney was the hottest place on Earth.

Cool roofs have many benefits. They slash how much heat gets into your house from the sun, keep the air surrounding your home cooler, boost your aircon efficiency, and make your solar panels work more efficiently.

State governments could, at a stroke, penalise dark roofs and give incentives for light-coloured roofs. Scaled up, it would help keep our cities cooler as the world heats up. But outside SA, it’s just not happening.

Why won’t state governments act?

To date, our leaders show no interest in encouraging us to shift away from dark roofs.

In NSW, plans to ban dark roofs were axed abruptly in 2022 after pushback from developers.

The current NSW planning minister, Paul Scully, has now paused upgrades to the state’s sustainability building standards which would have encouraged light-coloured roofs. Other Australian states and territories have also paused the rollout of new, more ambitious building sustainability standards.

This is short-sighted for several reasons:

- it costs the same for a light- or dark-coloured roof

- owners will pay substantially higher electricity bills to keep their houses cool for decades

- keeping the building status quo makes it harder to reach emission targets

- dark roofs cut how much power you get from your rooftop solar, especially when it’s hot. This is doubly bad, as blackouts are most likely during the heat.

At present, SA is the only state or territory acting on the issue. Early this year, housing minister Nick Champion announced dark roofs will be banned from a large, new housing development in the north of Adelaide.

What’s at stake?

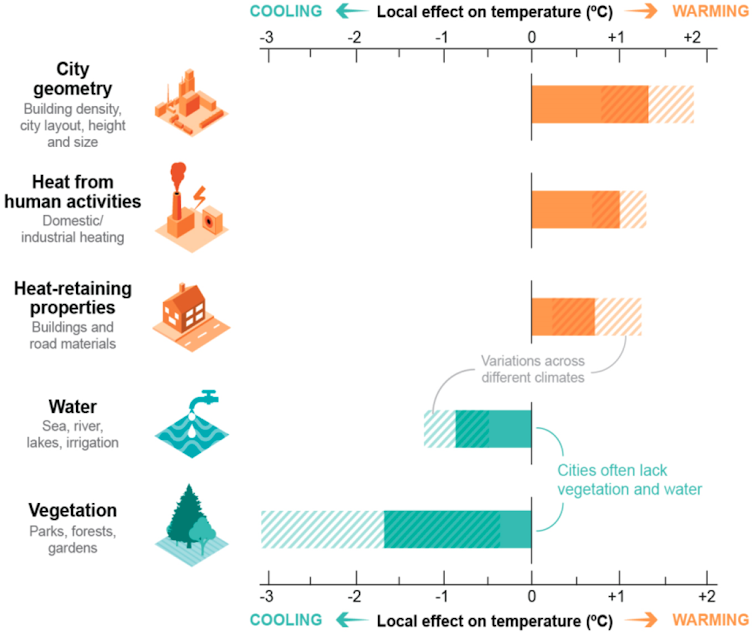

At present, the world’s cities account for 75 per cent of all energy-related carbon dioxide emissions. It’s vitally important we understand what makes cities hotter or cooler.

Brick, concrete, tarmac and tiles can store more heat than grass and tree-covered earth can, and release it slowly over time. This keeps the air warmer, even overnight.

Built-up areas also block wind, which cuts cooling. Then there’s transport, manufacturing and air-conditioning, all of which increase heat.

Before aircon, the main way people had to keep cool was through how they designed their homes. In hot countries, buildings are often painted white, as well as having small windows and thick stone walls.

The classic Queenslander house was lifted off the ground to catch breezes and had a deeply shaded veranda all around, to reduce heat.

But after aircon arrived, we gradually abandoned those simple cooling principles for our homes, like cross-ventilation or shade awnings. We just turned on air conditioning instead.

Except, of course, the heat doesn’t go away. Air conditioning works by exchanging heat, taking the heat out of air inside our house and putting it outside.

As climate change intensifies, it makes hot cities even hotter. Heatwaves are projected to be more frequent, including in spring and autumn, while overnight temperatures will also increase.

As cities grow, suburbs can push into hotter areas. The 2.5 million residents of Western Sydney live at least 50km from the sea, which means cooling sea breezes don’t reach them.

Sweltering cities aren’t just uncomfortable. They are dangerous. Extreme heat kills more people in Australia than all other natural disasters combined.

How can we cool our cities?

We don’t have to swelter. It’s a choice. Light roofs, light roads and better tree cover would make a real difference.

There’s a very practical reason Australians prize “leafy” suburbs. If your street has established large trees, you will experience less than half the number of days with extreme heat compared on residents on treeless streets. If you live in a leafy street, your home is also worth more.

Blacktop roads are a surprisingly large source of heat. In summer, they can get up to 75°C. Our research shows reflective sealants can cut the temperatures up to 13°C. Some councils have experimented with lighter roads, but to date, uptake has been minimal.

Cool roofs markedly reduce how much energy you need to cool a house. When used at scale, they lower the air temperatures of entire suburbs.

The simplest way to get a cool roof is to choose one with as light a colour as possible. There are also high-tech options able to reflect even more heat.

Soon, we’ll see even higher performance options available in the form of daytime radiative coolers – exceptional cooling materials able to reflect still more heat away from your house and cut glare.

Until we choose to change, homeowners and whole communities will keep paying dearly for the luxury of a dark roof through power bill pain and sweltering suburbs.![]()

Sebastian Pfautsch, Research Theme Fellow – Environment and Sustainability, Western Sydney University and Riccardo Paolini, Associate Professor, School of Built Environment, UNSW Sydney. Republished from The Conversation.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply