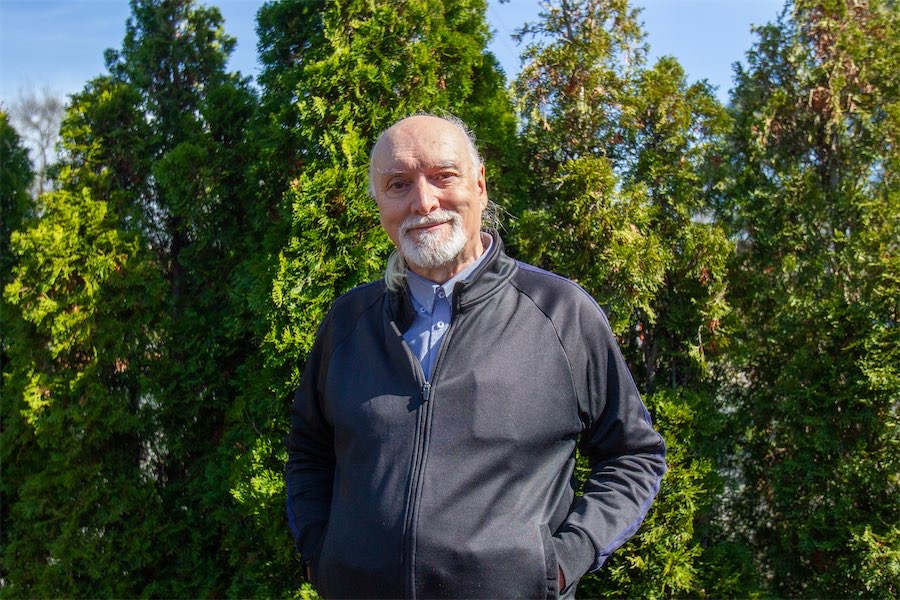

Historian Barry York has recently recorded his 500th oral history interview.

It was the story of a German man who had migrated to Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic and spent weeks in the Howard Springs quarantine facility in the NT.

Many of Barry’s interviews over the past 40 years have been on the topic of migration, a trend influenced by his own experience and stories from his uncle Joe, who had migrated from Malta in 1924 and had sponsored Barry and his parents to come to Australia in 1954.

Barry says he would go to his uncle’s house and sit transfixed as Joe recalled stories from the “old days” in Malta.

Barry says this curiosity was also fostered by his requests for information about his grandparents, who he never knew, in the form of bedtime stories, with his mum’s answers helping him to imagine what his grandparents would have been like.

His interest in preserving people’s stories never faded, and Barry went on to complete a PhD on Maltese migration to Australia before 1949.

“I started off by doing conventional research, you know, archives, libraries, print-based sources, and then it dawned on me that, […] there were people still alive, old people, who had come here before 1949,” he says.

“I interviewed some who had come in the 1910s, 1920s, and now, when you hear their voices, you’re hearing people who came here more than 100 years ago, which is quite extraordinary.

“You can deal with statistics about immigration and all that, but there’s always a human story behind it, and I thought, well, by recording the people who were behind the statistics, I’m humanising the story.

“The human voice is so distinctive and intimate, the accents, the intonations, can’t be captured really in print form, and above all else, the pauses can be telling.

“So to me, the interviews are about sound archiving, really creating a historical source for researchers based on listening.

“A lot of the people I’ve interviewed have been workers, working-class type people, and their stories are told and preserved through this method.

“All these stories would be lost, because none of these people would have written their autobiographies.”

Barry moved to Canberra in the late 1980s, and began doing contract work for the National Library of Australia’s (NLA) oral history collection, and for the ACT Heritage Library. He also worked as a historian at the Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House for 10 years, from 2006-2016.

He continues to do contract work, predominantly for the NLA, who commission specific stories.

He says one standout career moment was in 1997, when the NLA agreed to his pitch to interview former world heavyweight wrestling champion Mario Milano, his childhood hero.

“Growing up in Brunswick and working-class background and all that, I was a big fan of the pro-wrestling, it’s the WWE today, back then it had a bit more credibility.

“I recorded, over three sessions, several hours of Mario’s life.

“He ended up settling in Australia, so it was a migration story, but also he wrestled in America, and he was born in Italy, migrated to Venezuela after the war, like many Italians did.

“I would never have dreamed that I would record his story.”

Barry says a lot of work goes into preparing for oral history interviews, including a preliminary chat and a point-form outline of the important elements of their life to maintain a structure to the interview.

Then, he will draw up a question guide for them, which he will send to them so they can check if anything important has been neglected.

Barry says he takes a “whole life” approach to his oral history interviews, beginning with birth, parents, formative years, the voyage and settlement experiences, so interviews often take several hours and can sometimes take multiple sessions.

Barry hopes more people engage with recording their friends and families’ stories, especially now that technology makes it so easy.

“When I started, lucky I’m a big bloke, the recording equipment, it was called a Nagra-E, it weighed a tonne and it was reel-to-reel,” he says.

“Each reel went for 25 minutes, it was bad, because after 20 minutes you’d have to stop their flow, and then take a few minutes to change the takes.

“Now it’s fantastic, the technology is wonderful.”

Barry says he also helps out a lot with those who reach out asking for tips on how to conduct the oral history interviews, always gratis.

“I’m really committed to this work,” he says.

“It’ll be my most important legacy professionally.”

Barry’s work is accessible for research, personal copies and public use. Visit nla.gov.au/collections/ to view the York Collection.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply