IN the cultural warfare over whether January 26 should be retained as Australia Day, survey results are deployed like guided missiles. But what do Australians really think about the continuing debate?

A recent study undertaken by the Institute of Public Affairs found that three-quarters of Australians agreed that Australia Day should be celebrated on January 26.

In a survey taken late last year, before the annual Australia Day debate commenced, the Social Research Centre asked members of its Life in Australia research panel a similar question:

To what extent do you agree or disagree that 26 January is the best day for our national day of celebration?

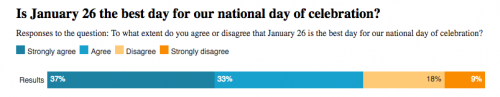

And from the 2167 responses, it received similar results: 70 per cent of respondents agreed (37 per cent strongly agreed/33 per cent agreed).

But this is where the story becomes interesting.

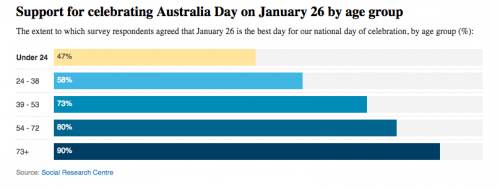

Support for January 26 increases with age. It is 73 per cent for Generation X (39-53 years) and 80 per cent among Baby Boomers (54-72 years). Among the Silent Generation (73 years or older), support for January 26 is nearly unanimous (90 per cent). But it is notably lower among the younger generations at 47 per cent and 58 per cent for Generation Z (aged 23 years or younger) and Millennials (24-38 years).

These results may explain why the ABC shifted its Triple J Hottest 100 away from January 26 after taking a poll in which 60 per cent of the 65,000 who voted supported the move.

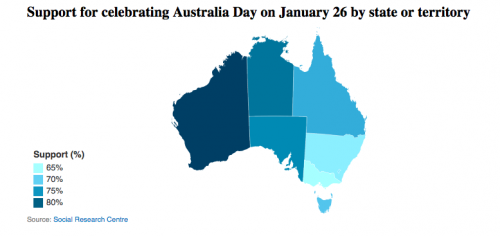

Support was also lower among those with a university degree (55 per cent) compared to those without (75 per cent). In terms of geography, support for January 26 was highest in Western Australia (83 per cent) and lowest in Victoria (65 per cent), and higher in the regions (78 per cent) than the capital cities (66 per cent). These results seem consistent with what we know about the patterns of progressive and conservative political values in Australia.

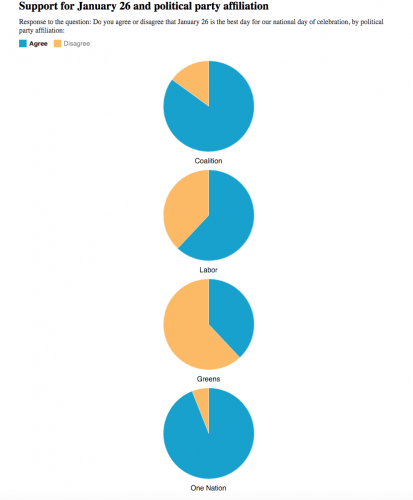

There are stark differences according to party affiliation. Support is highest among Coalition (85 per cent) and One Nation (94 per cent) supporters compared with 62 per cent of Labor supporters and just 38 per cent among Greens. On these results, perhaps the federal Labor Party’s present support for Australia Day might eventually come under pressure from within.

Those who disagreed that January 26 was the best day for our national celebration were asked:

On which day do you think Australia should have its national day?

Ten options were offered or an alternative could be nominated.

Reconciliation Day on May 27 – the anniversary of the 1967 referendum – was the most popular alternative at 24 per cent. It was followed by January 1, Federation Day (18 per cent). Somewhat bizarrely, 15 per cent of those opposed to January 26 being the date nominated May 8, because it sounds like “mate”. At present, no date clearly stands out as a popular alternative to January 26 as Australia Day.

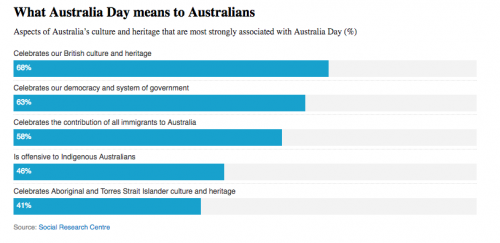

To gain a better insight into what January 26 actually means to Australians, we then asked a series of questions to explore which aspects of Australia’s culture and heritage were most strongly associated with Australia Day.

Just over two-thirds (68 per cent) of respondents agreed that January 26 celebrated our British culture and heritage. 63 per cent believed the current timing was a celebration of our democracy and system of government. And 58 per cent believed it celebrated the contribution of all immigrants to Australia.

The view that Australia Day recognised the contribution of all immigrants to Australia received stronger endorsement from those born overseas (65 per cent) than the Australian born (55 per cent). This suggests that the long-standing official Australia Day emphasis on unity in diversity has to some extent spoken to their sense of belonging. There is no other date in the Australian calendar that could be considered to represent the contribution of migrant communities.

The association of Australia Day and British culture and heritage was highest in New South Wales (73 per cent). This possibly reflects the particular significance of January 26 for the history of that state, but it is still below the levels observed in the Australian Capital Territory – 81 per cent – and the Northern Territory – 77 per cent. The association with British culture and heritage is highest amongst Coalition and One Nation supporters, at 73 per cent and 71 per cent respectively. For the Silent Generation, the celebration of Australia Day on 26 January is particularly evocative of British culture and heritage: more than four out of five agreed.

Official proponents of Australia Day have fudged the association of January 26 and Britishness as far back as the 1988 Bicentenary. They have more often emphasised diversity and belonging. Yet, fewer respondents accepted that the day was a celebration of migrant contributions relative to its association with British heritage.

In a similar vein, only a minority – although a large one (40 per cent) – believed January 26 celebrated Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture and heritage. This proposition is rejected most strongly by Labor and Greens supporters, those living in the capitals and the young.

Yet perhaps the most striking of all our findings is that 45 per cent of respondents agreed the day was offensive to Indigenous Australians. This figure is higher than that found in an Australia Institute poll of January 2018, which put the figure at 37 per cent.

The survey also found that women (49 per cent) are more likely than men (42 per cent) to see things this way, possibly reflecting the modern pattern for women to have more progressive political views. Those with a university degree (59 per cent), Victorians (51 per cent) and capital city residents (48 per cent) were also more likely to hold this opinion. And the party divide on this issue is clear. Labor and Greens (50 per cent and 75 per cent) supporters are much more likely to agree than Coalition and One Nation voters (32 per cent and 12 per cent).

Nearly three in ten (29 per cent) of respondents who agree with having Australia Day on January 26 also recognise the date is offensive to Indigenous people. It seems that many of us are sensitive to their objections, but not concerned enough to want to change the date. Australians incorporate in their historical consciousness a range of perspectives on the Australian past, and their significance for present-day commemoration, even when they are apparently in conflict with one another.

So what factors are at play here? One school of thought is that many Australians are mindful of the day’s negative connotations, but place a high value on it because it is an important marker in the calendar. The attachment to this last summer public holiday before the school year starts possibly outweighs concern about offence. Previous research has shownthat when people were asked to associate three words with Australia Day, the favourites were “barbecue”, “celebration” and “holiday”.

Still, the mix of attitudes we have uncovered seems likely to ensure the day remains contentious. Any expectation that January 26 might perform a similar kind of civic function to July 4 (Independence Day) in the United States or July 14 (Bastille Day) in France is fanciful.

It may be that the fortnight or so surrounding Australia Day is evolving into an annual season in which some of the deepest paradoxes of Australian identity play out in public.

is a professor of history at the Australian National University and Darren Pennay is the founder of ANU’s Social Research Centre. This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply