In the first of a two-part critical analysis of the October 6 ACT Budget, JON STANHOPE and Dr KHALID AHMED discover that the cash deficit in the ACT’s general operating activities means the government will have no option but to borrow to pay its interest costs.

THE 2021-22 Budget was framed in the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic and purportedly responds to its economic impacts.

The ACT’s economy has performed relatively well through the pandemic compared to other jurisdictions in Australia.

But the relatively better economic conditions in the ACT are reflective of a high public-sector labour force and there have certainly been adverse impacts on the territory’s small businesses and households reliant on casual jobs in the hospitality and service sectors.

The recent lockdown, the effects of which are not reflected in the June accounts, will have a more significant impact on the economy in general and on those sectors in particular.

Indeed, when announcing the Budget, Chief Minister and Treasurer Andrew Barr is reported to have said: “Right now, the territory economy would be in reverse. The September quarter will undoubtedly be a quarter of negative growth, and so we need to turbo charge the remaining three quarters of the year if we’re going to see the economy grow over the full fiscal year 2021-22”.

In this context, deferral of the Budget by five weeks from August 31 to October 6 was sensible and enabled the government to respond to the emerging conditions with appropriate adjustments to the Budget.

The government’s claimed thinking is reflected in the Treasurer’s reported statement that “a lot’s going to hinge on what we think are going to be the two major drivers of the economic recovery. One will be public investment – hence our infrastructure program in our Budget – and the other will be household consumption.”

In support of this claim, the government pointed to an infrastructure program of just under $5 billion. Subsequent public reporting has generally reflected the Budget’s focus on “turbo charging” the economy in response to the effects of covid and a general acceptance of the operating deficit and the increase in net debt as a “cost” that must be borne.

We acknowledge that this would be a reasonable supposition if the Budget actually incorporated a real and effective response to the impacts of the pandemic.

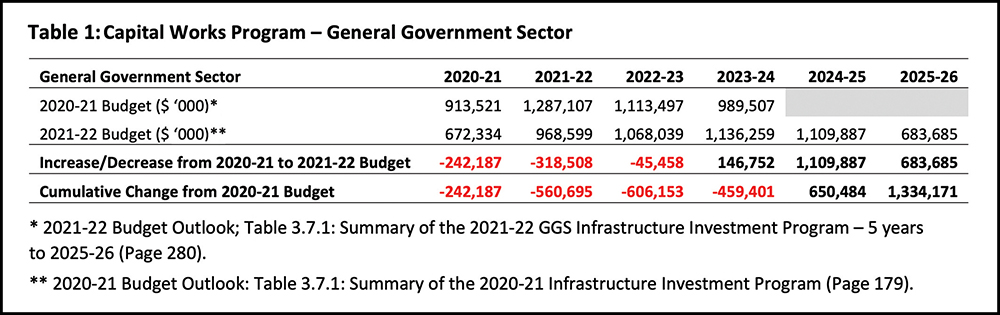

Unfortunately, an examination of the Budget reveals that the claimed increase in the capital investment program from $4.3 billion in the 2020-21 Budget to $5 billion in the 2021-22 Budget is misleading.

For a start, the 2020-21 program was over a period of four years, whereas the program announced in the 2021-22 Budget is over a five-year period. Excluding the $684 million allocated for 2025-26, and comparing the respective four-year programs, the allocation in the recent Budget is in fact lower than in the 2020-21 program (see Table 1).

Further, contrary to the claimed objective of “turbo charging” the economy in the next three quarters through infrastructure investment, the expenditure forecasts for 2021-22 and 2022-23 are $319 million and $45 million lower, respectively, compared to the forecasts in last year’s Budget.

Further, contrary to the claimed objective of “turbo charging” the economy in the next three quarters through infrastructure investment, the expenditure forecasts for 2021-22 and 2022-23 are $319 million and $45 million lower, respectively, compared to the forecasts in last year’s Budget.

To make matters worse, while the estimated outcome for the 2020-21 capital works expenditure has not been reported explicitly in the infrastructure chapter, the cash flow statement suggests a capital works underspend of approximately $242 million.

In summary, the detailed tables in the Budget papers indicate that the government will be spending $606 million less on capital over the period 2020-21 to 2022-23.

Taking into account the underspend and withdrawals/deferrals, the first actual increase in capital expenditure in this Budget is in 2024-25. If the government intended to “turbo charge” the economy through infrastructure investment, it would have been better to simply adhere to the undertakings and estimates in last year’s Budget.

It is clear that because of its limited capacity the Budget has, other than addressing some past neglect, fallen well short of its stated objective of “turbo charging” the economy. In fact, on our assessment, the ACT’s Budget was, before the pandemic, in the worst position of any state or territory and, as such, least able to respond to its effects.

DEBT

Worryingly naive view of ‘cheap’ borrowing

‘The government will have no option but to borrow to pay its interest costs’

FOLLOWING release of the Budget, the Transport Minister Chris Steel is reported to have said that “debt has never been this cheap. Financing costs have never been lower, and interest rates are also at a record low”.

It is worryingly naive to regard the availability of cheap debt in itself as a justification for borrowing. It is important firstly to examine how the debt is being utilised as well as the capacity to sustain the debt.

The operating Budget of an entity typically includes non-cash expenses, for example, depreciation and provisions for employees’ entitlements that require funding in the future.

If the operating Budget is to enter into deficit, it is important to maintain a balanced cash budget or a surplus so that the entity does not need to resort to borrowing to pay employees or to pay interest on previous borrowings.

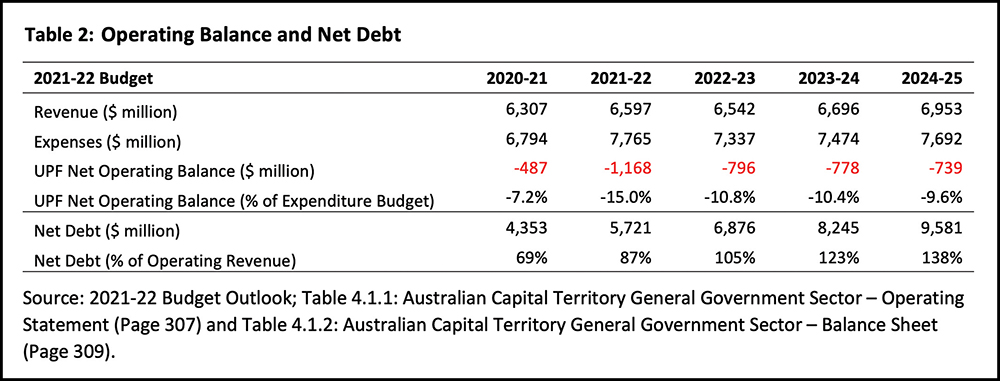

The latter is a particularly alarming scenario with a clear risk of a debt spiral. In 2021-22, the cash deficit in the ACT’s general government operating activities is forecast to be $328 million, while interest costs will be approximately $229 million. This means that the government will have no option but to borrow to pay those interest costs, and more.

The 2021-22 Budget forecasts a record headline operating deficit of $952 million for 2021-22 and deficits averaging around $520 million across the forward estimates (see Table 2).

However, under the measure agreed by the Australian and all state and territory governments for reporting on an operating budget, the ACT Net Operating Balance for 2021-22 is forecast to be negative $1.168 billion. Across the forward estimates, on this uniform presentation measure, deficits are forecast to range between $796 million to $739 million.

However, under the measure agreed by the Australian and all state and territory governments for reporting on an operating budget, the ACT Net Operating Balance for 2021-22 is forecast to be negative $1.168 billion. Across the forward estimates, on this uniform presentation measure, deficits are forecast to range between $796 million to $739 million.

To put that in perspective, relative to the forecast operating expenditure of $7.765 billion, the deficit is 15 per cent of the operating budget. This is the highest of all the states and territories, with Victoria forecasting a deficit of 13.5 per cent and NSW 8.4 per cent.

The ACT’s net debt is forecast to increase across the forward estimates to $9.6 billion in 2024-25, which is 138 per cent of the forecast operating revenue.

HEALTH

Health boost doesn’t make up for what was taken

“The capacity of the system will be limited due to the shortage of clinical and allied health staff nationally.”

THE government has made much of claims that the 2021-22 Budget provides a significant boost in spending, including on health.

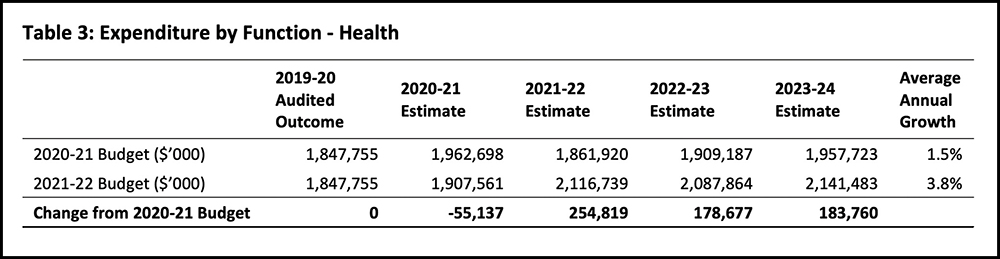

The increase as shown in Table 3 is an increase in the base health expenditure in the order of $180 million a year.

Over the past several years, we have highlighted the relatively lower priority given to health through (a) abandonment of the $1.3 billion hospital redevelopment program, and the deferral of the scaled-down project of $500 million; and (b) a reduction of one per cent a year in appropriate growth funding that meets the health needs of a growing population and increasing costs of technology.

Over the past several years, we have highlighted the relatively lower priority given to health through (a) abandonment of the $1.3 billion hospital redevelopment program, and the deferral of the scaled-down project of $500 million; and (b) a reduction of one per cent a year in appropriate growth funding that meets the health needs of a growing population and increasing costs of technology.

Both these factors resulted in an actual decrease in available hospital beds, unfilled staff positions, the worst waiting times in the emergency department, and some of the longest waits beyond clinically recommended times for elective surgery in Australia, leading to public concerns from frontline clinicians about the safety of our hospital system.

The increase in health funding, albeit only a proportion of what was earlier withdrawn, is welcome. Unfortunately, once the capacity in a complex system is degraded, it takes a concerted effort over a long time to rebuild that capacity.

In the current environment in particular, the absorption capacity of the system will be limited due to the shortage of clinical and allied health staff nationally. The estimated underspend in health of $55 million against the Budget provision in 2020-21 illustrates the point.

There are other areas that don’t fare well in this Budget with either decreased funding or inadequate growth across the forward estimates (eg environmental protection and social protection) or a decrease in allocation compared to the 2020-21 Budget estimates (eg education).

Jon Stanhope is a former chief minister of the ACT and Dr Khalid Ahmed, a former senior ACT Treasury official.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply