“To be trusted, integrity commissions have a key role in identifying where no corruption occurs and to be able to appropriately reassure the public that everything is actually above board,” writes political columnist MICHAEL MOORE.

THE crossbenchers in the federal parliament negotiated for the most effective possible legislation for an anti-corruption commission.

Other similar commissions provide a blueprint to optimise such commissions. However, with just two substantive reports after years of operation, can the ACT Integrity Commission provide such a model..

Along with a strong interest in prevention of corruption, transparency must be the prime focus of federal legislation. Education and deterrence of corruption was also a major plank in the legislation that established the ACT Integrity Commission.

In both reports on the website of the ACT Integrity Commission there has been no corruption identified. In fact, criticism has been levelled at other investigative groups including the ACT auditor-general and an Assembly committee. The Special Report – Sale of Block 30, Section 34, Dickson, also known as “Operation Raven”, for example, found no corruption.

In fact, the Integrity Commission determined to discontinue the investigation arguing “the commission is satisfied that the legal threshold for investigation was not met”. The commissioner went further in stating: “The commission is further of the view that many of the criticisms made by the auditor-general and the committee were not justified”.

The commission “found that the land sale process itself was adequate and complied with all necessary legal requirements. While there was an inappropriate lack of documentation surrounding some aspects of the transaction, there was sufficient material to enable the commission to confidently conclude that there was no reasonable suspicion of corrupt conduct on any person’s behalf”.

There was a similar story with regard to investigation “Operation Lyrebird” regarding a land deal in Glebe Park. The report concluded “the evidence does not provide grounds for a reasonable suspicion” that would suggest “any official acted corruptly in connection with the acquisition of Block 24”.

In February, after a scathing report regarding the upgrading of Campbell Primary School, the ACT Integrity Commissioner, Michael Adams KC pointed out that probity issues with the ACT government’s procurement processes are likely to be endemic.

He also told an Assembly committee that the cost to fully investigate them would be trivial compared to the money spent on the contracts. This investigation remains ongoing.

A great deal of faith is put in the hands of anti-corruption commissions by the public. Along with royal commissions, Assembly committees, auditors-general and other instruments of government they have a key role in exposing corruption.

To be trusted, they also have a key role in identifying where no corruption occurs when issues are raised and to be able to appropriately reassure the public that everything is actually above board.

The legal nature of integrity commissions and their investigative powers are not dissimilar to those of a royal commission. However, the focus can be much broader and referrals ought not be restricted to a mandate by the government.

One of the key elements called for by the federal Greens and independents, including Senator David Pocock, is the ability for the federal anti-corruption commission to have the power of self-referral. The legislation introduced by Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus includes this provision even though it means that the government does lose a significant amount of control.

When Dreyfus introduced the legislation it became clear he was looking for an effective anti-corruption commission. It will be able to examine serious or “systemic corrupt conduct” across the Commonwealth including ministers, statutory office holders, employees and contractors.

Oversight, as expected by the crossbenchers, should be at the parliamentary level in order to remove the appearance of corruption at party political level. Additionally, appropriate funding is fundamental. At the moment this has been set at $262 million over four years.

Sticking points in negotiations for crossbenchers have been protection of whistleblowers and the use of public hearings. Consistent with promises by the government to work with members across the parliament, the whistleblower issue has been incorporated in the legislation and other legal protections have been strengthened. There is still some debate over whether public hearings should only be used in “exceptional circumstances”.

These issues will be debated when the legislation is examined by a parliamentary committee.

The parliamentary champion for the issue of an anti-corruption commission has been the independent member for Indi, Helen Haines. Her consistent advocacy has paid off. Although Dreyfus will get credit for introducing effective legislation, it is Haines and the other crossbenchers who have been the catalyst.

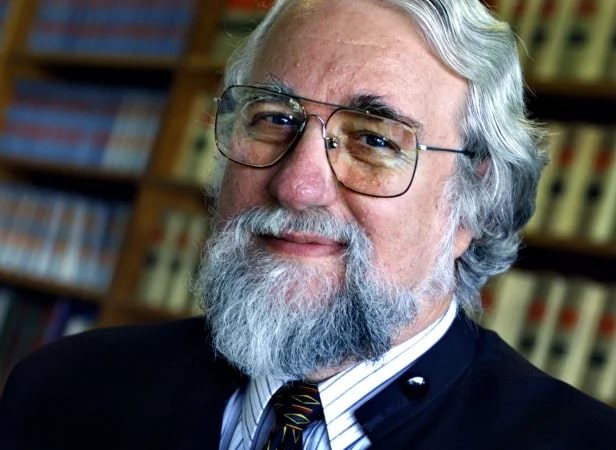

Michael Moore is a former member of the ACT Legislative Assembly and an independent minister for health. He has been a political columnist with “CityNews” since 2006.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply