Book reviewer COLIN STEELE writes of a biography and an autobiography that reflect tales of riches-to-rags and rags-to-riches stories.

NICHOLAS Shakespeare’s new biography, “Ian Fleming: The Complete Man” and Patrick Stewart’s autobiography “Making It So”, reveal the men behind James Bond and “Star Trek. The Next Generation”.

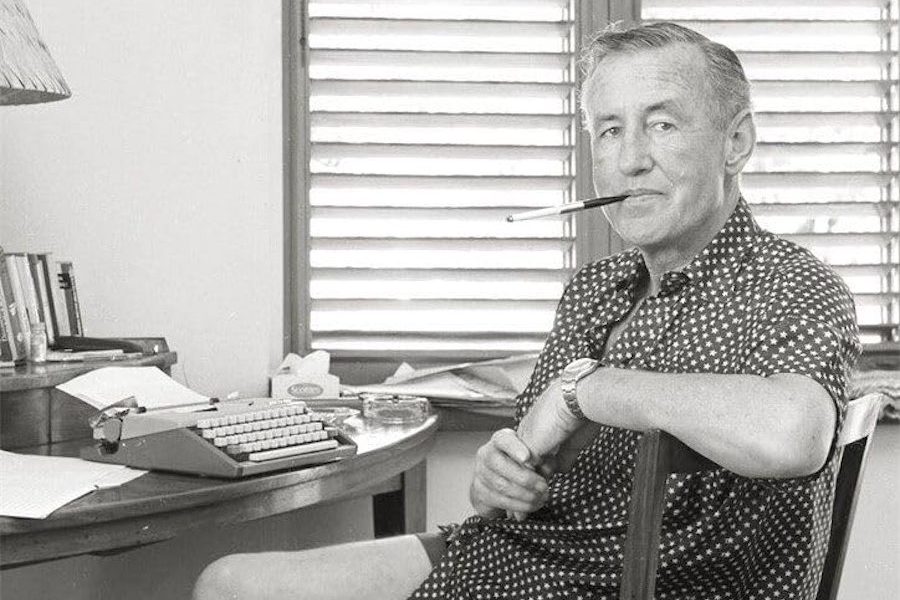

There have been several previous biographies of Ian Fleming, but Shakespeare’s has the advantage of unprecedented access to the Fleming archive. Fleming will forever be coupled with James Bond, but Shakespeare aims to give a picture of “the complete man”.

Fleming, from a wealthy background, had a difficult childhood. His father was killed in World War I and he grew up impacted by a “monstrous” mother and a more popular elder brother, Peter.

He left Eton under a cloud and similarly at Sandhurst after contracting gonorrhoea. A period as a stockbroker was followed by journalism in the 1930s, before an impressive career in Naval Intelligence in World War II, which Shakespeare covers with much new detail and which provided Fleming with an authentic background for the Bond novels.

Patrick Stewart, now 83, begins his autobiography with an epigraph from Shakespeare: “The web of our life is of a mingled yarn, good and ill together”. His life, like that of Fleming, was a mingled one. In contrast to Fleming, however, Stewart came from an impoverished working-class background in rural Yorkshire.

His was another dysfunctional family, with his mother often assaulted by a father with World War II PTSD and an alcohol problem.

Stewart reflects: “The future 24th century commander of the ‘Enterprise’ grew up with neither a toilet nor a bathroom in his house… It’s taken me decades of analysis… to understand and cope with the impact of the violence, fear, shame and guilt I experienced as a child”. He believes he copied “Jean-Luc Picard’s stern, intimidating tendencies” in “Star Trek” from his father.

Similarly, Fleming’s background imbued the Bond novels with “sex, sadism and snobbery”, as Paul Johnson described them in a 1958 review of “Dr No”.

Shakespeare covers Fleming’s numerous affairs. Fleming evaded marriage until 1952 when he married his mistress, the pregnant Ann Charteris, previously married to Lord Rothermere.

Their love of flagellation is reflected in Fleming’s 1953 debut novel “Casino Royale”, launched amidst the “Spam-munching gloom of Attlee’s Britain”.

Fleming’s relationship with Ann, who was accustomed to wealth, became one of “piranha shoals of recrimination”, alleviated by episodes of mutual flagellation.

Fleming once commented: “My profits from ‘Casino Royale’ will just about keep Ann in asparagus through Coronation week”. Ann’s intellectual coterie, which included her lover, future Labour Party leader, Hugh Gaitskell, scorned “Casino Royale”, forcing Fleming to call it an “oafish opus”.

Bond book sales only really took off globally after the 1962 “Dr. No” film with Sean Connery. Fleming, a 70-a-day cigarette smoker, did not have long to enjoy the royalties. He died of a heart attack in 1964 at the age of 56. Fleming had reflected, “Ashes, old boy. It’s just ashes . . I’d swap the whole damned thing for a healthy heart”.

The world thus missed the Bond novel, with, in Fleming’s words, “one final fatal Australian blonde”.

Shakespeare ends his definitive biography in 1964, apart from covering the suicide in 1975 at the age of 23 of Ian and Ann’s son Casper, another tortured individual.

Patrick Stewart reflects back on his life with a little more joy than Fleming, although one senses that he takes more pride in the first half of his life when he had a significant career in British theatre, including 60 productions of the Royal Shakespeare Company.

Nonetheless, he acknowledges the benefits of the wealth and fame, including a knighthood, which arrived from his starring roles in the “Star Trek” and “X-Men” series.

Stewart’s memoir essentially falls into two parts, his acting life before and after “Star Trek”. Trekkies may not be interested in the theatrical first half, while the minutiae of “Star Trek” detail in the second may only appeal to that group.

Stewart’s personal relationships, post Yorkshire with his parents and his three marriages, which significantly impacted his relationship with his two children, are largely glossed over – no boldly going here. He comments: “In a life chock-a-block with joy and success, my two failed marriages are my greatest regret”.

“Making It So” is an ultimately engaging rags-to-riches story, while “The Complete Man”, at the personal level for Fleming, is more riches to rags. However, readers of both books will undoubtedly wish, as Picard would put it, to engage with their lives.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply