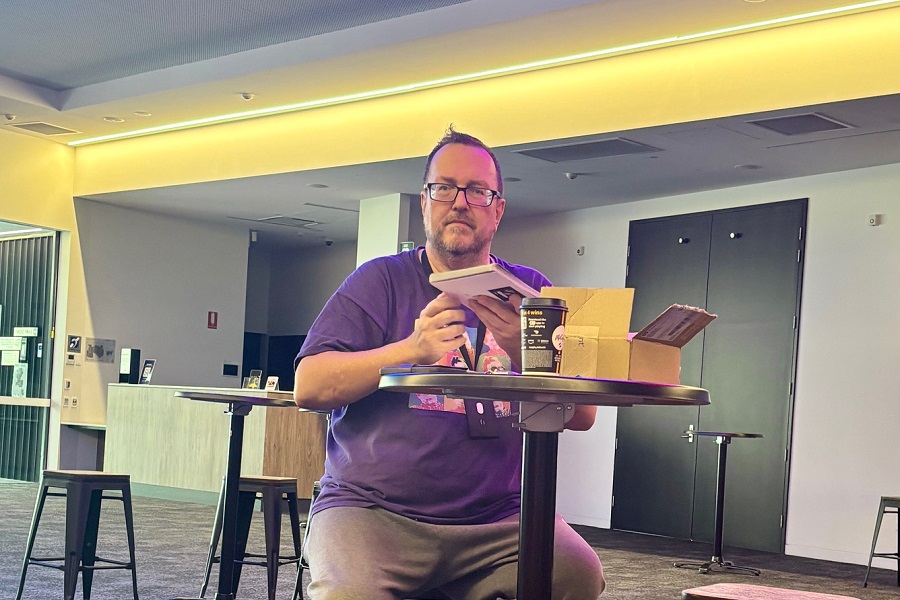

Photography / Kooragang Island by James Rhodes and Ngulagambilanha (“On Returning”) by Jessika Spencer. At Photo Access until August 3. Reviewed by BRIAN ROPE.

These two new exhibitions at Photo Access are very different but share something significant.

In his Kooragang Island show artist James Rhodes challenges traditional representations of that island’s landscapes, on unceded lands of the Awabakal and Worimi peoples, and invites us to appreciate and respect the delicate balance of its remarkable wetlands’ environment.

In Ngulagambilanha, Wiradjuri artist Jessika Spencer intimately shares details of Aboriginal cultural practices and, through them, explores her cultural identity.

Spencer is a First Nations photographer, weaver, writer and activist. Here she shows us her photography and some fibre art pieces. The imagery shows us moments of cultural practices such as ceremonies, weaving and gathering. The photos are straightforward, colourful and pleasing to look at.

The artist’s two sculptural pieces use contemporary weaving techniques employed by Aboriginal people and are also most pleasing to the eye. For Spencer, being an Aboriginal woman, culture and art go hand in hand. This exhibition reveals something of that to us.

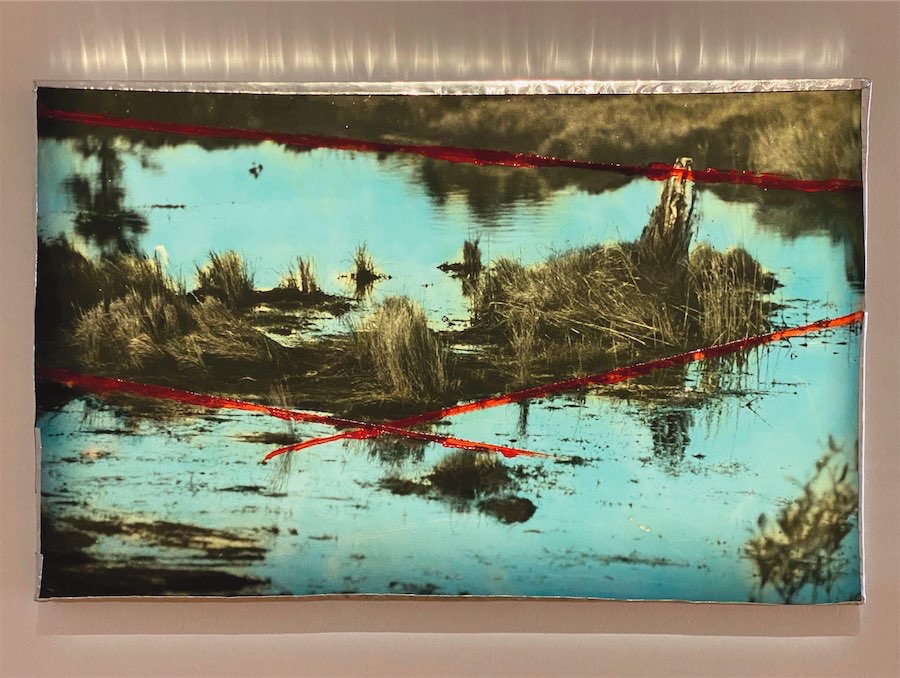

Multidisciplinary artist Rhodes is known for his photomedia, painting and sculpture. Here he combines abstract photography, hand-coloured prints and projection to reveal something of his perception of the world around him.

From a distance as I walked into the gallery at Canberra’s centre for photography, film, video and media arts I wondered where the photography was, but as I moved closer to the first works I saw that the underlying images in them were photographs.

Questions I then heard others asking included why are there red crosses over the pictures? Why are they framed with aluminium foil? Why are there differently sized white borders on most of the works, sometimes not on all sides of the pieces?

Speaking with the artist as we stood alongside one of the works ensured I gained some understanding. Photographers who worked with film back in the day very probably marked up their proof sheets for printing with hand-applied, coloured grease pencil lines, thus creating a lasting reference. So, Rhodes is incorporating subtle symbols and ambiguous motifs into his works.

The use of aluminium foil is an artful reference to the clearing, draining, filling and dredging that significantly impacted the island landscape. His blank white spaces are intended to make us aware of the adjacent areas we cannot see.

The good news is that the Kooragang Wetlands have progressively been very much restored, redressing the loss of fisheries, shorebirds, threatened species and other wildlife habitat in the Hunter Estuary due to clearing, draining and filling over the past 200 years.

The artist’s photos have been overpainted, but they clearly are there. Belle Beasley’s room sheet essay elaborates and is well worth reading after viewing the exhibition – or while you are there if you need assistance to interpret the artist’s messages.

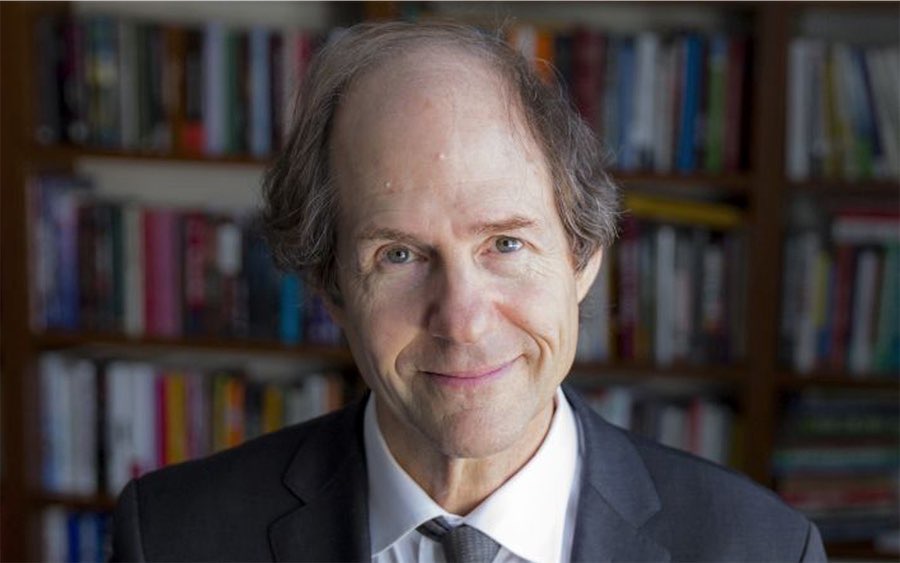

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply