“Voting is a social responsibility. Australia’s 90 per cent plus turnout is, on average, 30 per cent higher than most countries in recent elections… We should be proud that Australians take their social responsibility seriously,” writes political columnist MICHAEL MOORE.

It is a century since compulsory voting was introduced federally in Australia.

Compulsory voting is part of the proud history of electoral innovation in Australia. Even more importantly, it has also played a role in limiting the extreme polarisation that has been the hallmark of recent overseas elections.

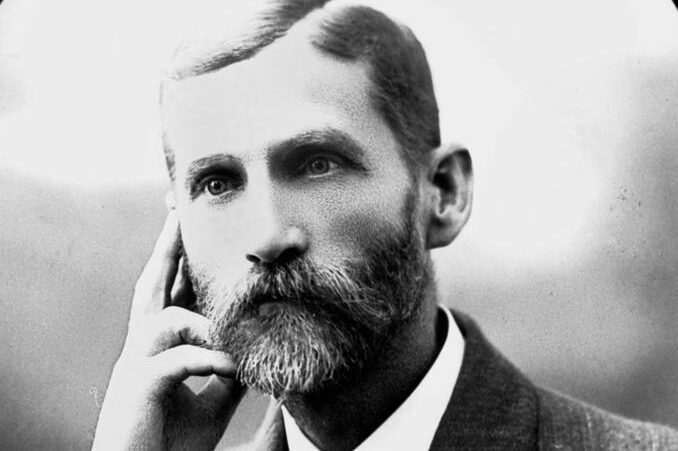

The first use of compulsory voting was in Queensland in 1915. Liberal premier Digby Denham was concerned about the impact unions were having in getting voters to the polling booths and thought his government could restore a level playing field. Ironically, he lost that year’s election.

Turnout in the federal election in 1919 was 71 per cent and dropped to 60 per cent in 1922. Although concerns were raised, the major parties were not prepared to risk voter backlash on the subject. Instead, a private members bill was introduced by Tasmanian National Party senator Herbert Payne and supported in the House of Representatives by Edward Martin, a National Party member from Perth.

It was only the third private member’s bill in the federal parliament. The bill passed quickly through both houses. The impact was immediate with more than 91 per cent of Australians turning out to vote. Since that time, Australia has always had more than a 90 per cent turnout of voters.

The simplified term “compulsory voting” is somewhat misleading. No-one can force a person to actually vote. A voter has the option of putting in a blank ballot paper. And, although uncommon, scrutineers tell me that informal ballot papers are sometimes decorated with quite artistic works, or covered in profanities.

However, the term “compulsory voting” is in the lexicon, and it is too late to adopt an alternative term such as compulsory attendance at polling booths.

According to the Australian Electoral Commission there are 32 countries that currently mandate voting, including 10 of the 30 OECD countries. Similar Anglophone democracies do not require citizens to vote and have much poorer voter turnout. At their last elections, the UK had just 52 per cent of registered voters turnout; Canada, 62.6 per cent; NZ, 77.5 per cent and the US 66 per cent.

In some of the countries that do have compulsory voting legislated, such as the Netherlands and Italy, it is not enforced. At their last elections the Netherlands had 77.7 per cent turnout and in Italy in 2022 the turnout was just 64 per cent.

Voting is a social responsibility. Australia’s 90 per cent plus turnout is, on average, 30 per cent higher than most countries in recent elections.

When a government takes power in Australia, it is with the mandate not just of a majority of voters, but although there are rare exceptions, the majority of citizens. We should be proud that Australians take their social responsibility seriously.

Paul Strangio, writing in The Conversation, points out that compulsory voting came on top of the other Australian electoral innovation of the secret ballot (in other countries sometimes called the “Australian ballot”). The Hare-Clark system, as introduced in Tasmania and used in the ACT is a more recent Australian electoral innovation. It has been modified to increase power in the hands of voters.

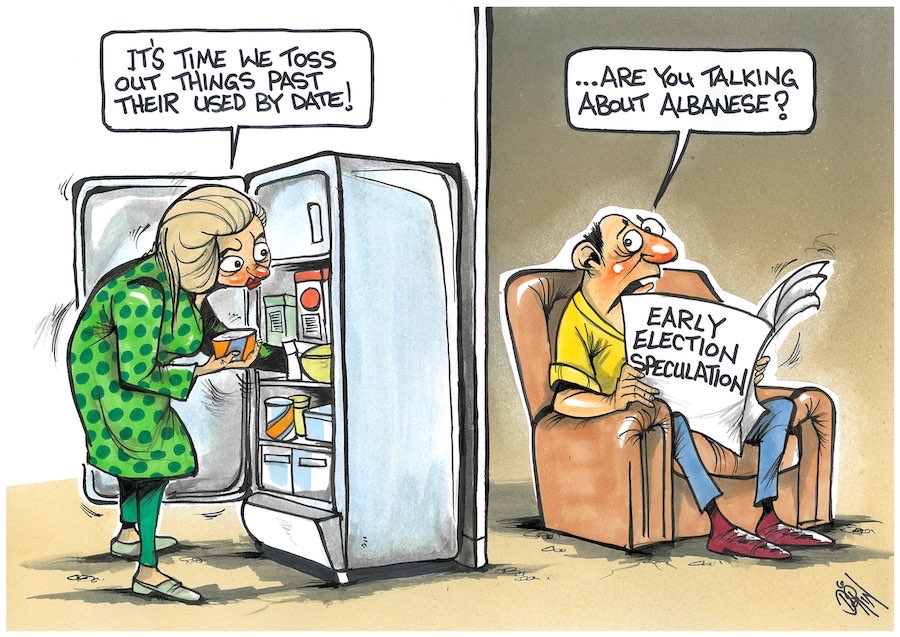

Strangio also argues that compulsory voting “affords legitimacy to election outcomes in this country” and “produces a socially even turnout”. The socially even turnout is significant. The polarisation that can be observed in the current presidential elections in the US is partially built around the need to bring voters to the polling booths. Extreme views appeal to some who might otherwise not come out to vote.

As Stranglo argues, compulsory voting “exercises a moderating influence because it ensures it is not only impassioned partisans at either end of the political spectrum who participate in elections. This, in turn, means they are not the chief focus of governments and political parties”.

It should also be noted that a significant strength of our system is the trust in the Australian Electoral Commission that is non-partisan, and a fair arbiter of the system. The trust is engendered even further with the “light touch” way they follow up people who have not voted.

The strongest advantage of mandating voting is that governments and political parties when developing and implementing their policies must largely consider what is in the interest of all sectors of the community.

Electing governments by all of the people may well explain why compulsory voting has such strident support in more than 70 per cent of Australians.

Michael Moore is a former member of the ACT Legislative Assembly and an independent minister for health. He has been a political columnist with “CityNews” since 2006.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply