DRAWING from life is one of the foundation experiences of training to be an artist; it is an exercise in teaching the hand to move in tune with the eye, to translate not just the shape of the body but the energy held within it, the potential and possibilities of a body held still for only a relatively short period of time. So what happens if the model is dead?

Printmaker Tony Ameneiro has produced a stunningly beautiful and energetic exhibition from a drawing residency carried out at the JT Wilson and Shellshear Museums at Sydney University. Both are specialised collections of human anatomy, full of bodies donated to science for educational and research purposes. Such donations are important for training medical professionals and to find solutions to disease and illness. The collections treat them with the utmost respect: no camera or recording equipment can be used in the museums.

These strict rules gave Ameneiro the creative constraint he needed. He would spend four to five hours drawing in the museum, then take the drawings back to his studio. Instead of working up the images into elaborate print editions, moving the marks through a number of technical stages, he explored more direct printmaking techniques that produced fewer prints, but more exciting, immediate results: drypoints, monotypes, and digitally-altered pigment printing.

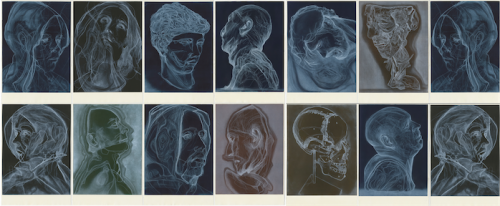

“Head over Head” is full of life. There is a long wall of white-inked line drawings of heads (“Heads over Heads”, 2016) layered on deep shades of blue and grey, invoking X-rays, or swirling jellyfish in the bottom depths of the sea. The sombre tones are what we might expect from a respectful close observation of cadavers. The other walls, though, unfurl bright colours, rich combinations built up with tool and hand.

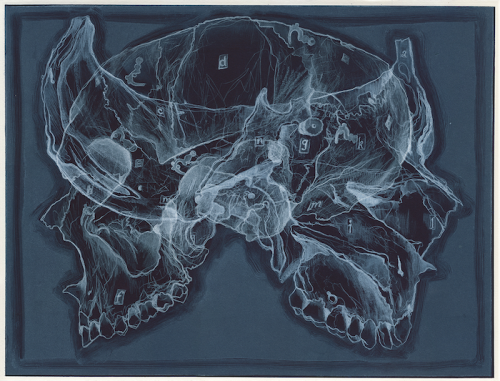

“Head over Head #1-#4“ (2015) are vertical mirrorings of heads, drawn in exquisite detail with the drypoint needles, then surrounded by swirls of hand-pushed ink that leave a palpable aura of the artist’s energy. Other multiple plate combinations are layered just out of kilter in clashing tones (“Wilson Head over Head” (2016) or flipped to form classical references – “Wilson Head #12 (Janus version) (2016″).

Ameneiro’s fabulous drafting skills restore a sense of life to these medical specimens, but he does not let us forget their purpose. Some heads have parts of their skull missing, others are actually skulls, complete with pins, hinges and stands. Nothing is gross, everything conveys a deep sense of respect felt by the artist for their contribution to contemporary advances in medicine.

The pigment print (also known as a Giclee print) is a form that deeply divides printmakers, because it is often used as a high-end reproduction technique that undermines the hard work that goes into hand-printing. However, in this situation Ameneiro has used the technique thoughtfully. The original drawing (“Wilson Head #13” – also in the exhibition, in a side room that is easy to miss, but don’t miss it) is sketched loosely in graphite and partially rendered using colour pencil in delicate warm tones, turned so that the prone head sits upright. When inverted, the colours shift to pale greens and glowing white, as if seen through a screen measuring heat and energy. The pigment ink is luminous, capturing some trace essence of humanness.

This is a celebration of mortality, of generation and regeneration; for me it celebrates the wonder of our human existence with more warmth than the recent NGA “Hyper Real” exhibition. The artist will give a floor talk at 2pm on March 10.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply