THE launch of the “Endeavour Voyage” exhibition yesterday (June 2) was a double coup for the National Museum of Australia.

First, as Arts Minister Paul Fletcher and NMA director Mathew Trinca were quick point out, the exhibition marking the 250th anniversary of Lieutenant James Cook’s 1770 passage up the nation’s east coast, which had been due to open in April before COVID-19 restrictions, turned out to be the perfect choice for Reconciliation Week as “a story we all thought we’ve known but didn’t know… a chance to look honestly at our past”.

Second, it was a sure sign that “we are really here, we’re not on Zoom”.

There can be no doubt that the museum has achieved something significant with this complex show, fully titled “Endeavour Voyage: The Untold Stories of Cook and the First Australians”, which fills the gaps in our understanding by showing us not just the perspective of Cook, Joseph Banks and the Endeavour crew as they passed along the east coast of Australia, but what the original inhabitants saw too.

Museum-watchers will remember the trouble the national institution got into during its fledgling years from former prime minister John Howard, who complained that there was too little shown of foundational British figures like Cook and Flinders and too much “black armband” history – this exhibition is a case of ‘be careful what you wish for’.

Imaginatively laid out by Queanbeyan’s Thylacine design company so that you can feel the difference between walking on wood (you’re on the ship) and walking on the land, visitors can explore the nooks and crannies to observe fascinating museum-style objects, like three fishing spears collected at Botany Bay in 1770 (displayed with newly crafted spears by Dharawul elder Rodney Mason), Banks’ travelling stove and – minister Fletcher‘s favourite – a 1970 Gregory’s Street Directory (he needed to explain to younger people present what that was) featuring the image of Cook on the cover.

Howard might be pleased with one aspect of the exhibition, however, in that it is partly a celebration of the way modern Australia can explain and discuss the issues.

But what issues they are.

As author Peter FitzSimons is quoted in the show as asking of Cook, “was he a hero, an anti-hero, a great man or imperialist villain?”

The answer could depend on where you’re coming from, although the NMA is keen to re-balance what has so far been a “one-sided narrative”.

Dharawal man and community representative from La Perouse, Ray Ingrey was on hand to answer questions about early encounters at Kamay Botany Bay, where things didn’t go well, with violence offered by the intruders and well-documented efforts to ignore newcomers on the part of the locals.

But another section of the exhibition is devoted to a more favourable encounter in Cooktown during June 1770, which the NMA believes can be regarded as an example of “the first act of reconciliation on Australian soil”.

This cordial entente, curator Shona Coyne believes, was made possible by the fact that local Aboriginal elders were strict about observing protocols stipulating that no blood be spilled on the spot where these first meetings took place – a genuine two-way engagement.

There are many traditional museum objects on show, including the 1776 James Cook portrait by Nathaniel Dance on loan from the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, a marble bust of Cook and botanical and zoological drawings by Endeavour crew members.

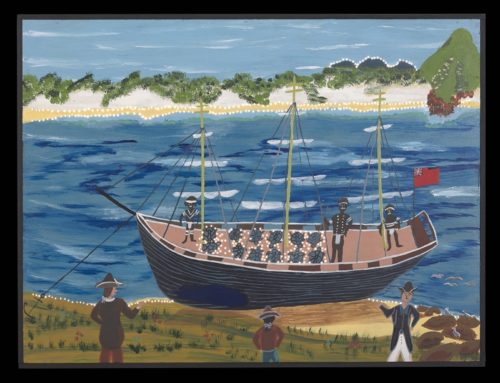

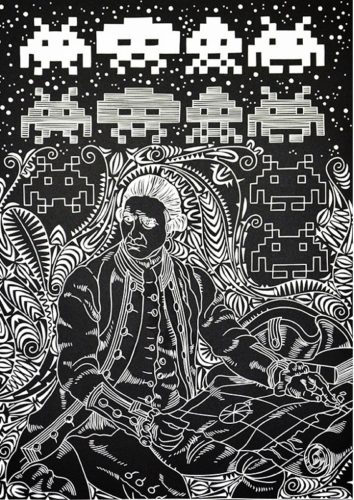

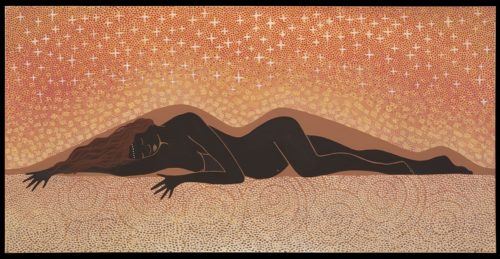

But interspersed with these are contemporary art works of breathtaking quality, the result of Federal government-funded workshops with Indigenous communities along the east coast.

There are also works by professional artists, not least Brian Robinson’s prize-winning satirical linocut, “By Virtue Of This Act I Hereby Take Possession Of This Land” and Cheryl Davison’s 2018 painting of Gulaga (Mt Dromedary on the south coast), making the point that where local people saw a woman’s curves, Cook saw a camel.

Central to “Endeavour Voyage” is a huge screen offering an immersive visual experience created by film maker Alison Page and director Nik Lachalczak, a series of filmed re-imaginings of the lives of the original people going about their business, then making first contact. Not only is there breathtaking footage of the coastal views that would have greeted the British sailors, but the way of life is shown, proving once and for all, in the words of a Monaro-Yuin elder, “Cook didn’t discover Australia, our people were already here.”

“Endeavour Voyage: The Untold Stories of Cook and the First Australians”, National Museum of Australia, Lawson Crescent, Acton, until October. Bookings of free, timed tickets at nma.gov.au

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply