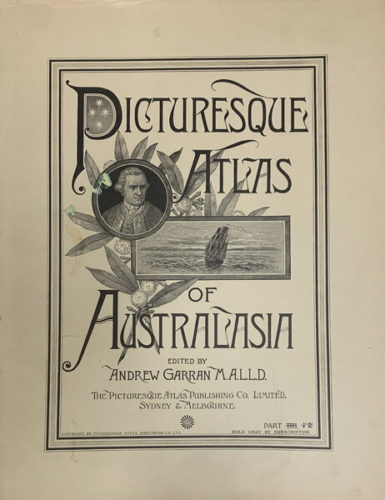

“A Nation Imagined: The Artists of the Picturesque Atlas” turns the spotlight on the 19th century publication that was the “Lonely Planet” of its era, giving its 50,000 subscribers a visual impression of life in Australia at the time.

It ended up as a three-volume fine art book and was seen by visitors to the world expositions in Melbourne and Chicago, where it won a medal.

As I found it during a walk-through with the animated and erudite Natalie Wilson, curator of Australia and Pacific Art at AGNSW, “The Picturesque Atlas”, published in supplements between 1886 and 1889, had international counterparts but only the Australasian publication used the term “atlas”, featuring maps as well as drawings and paintings.

Alas, with the global depression of 1890, the high subscription prices brought the publication to an end.

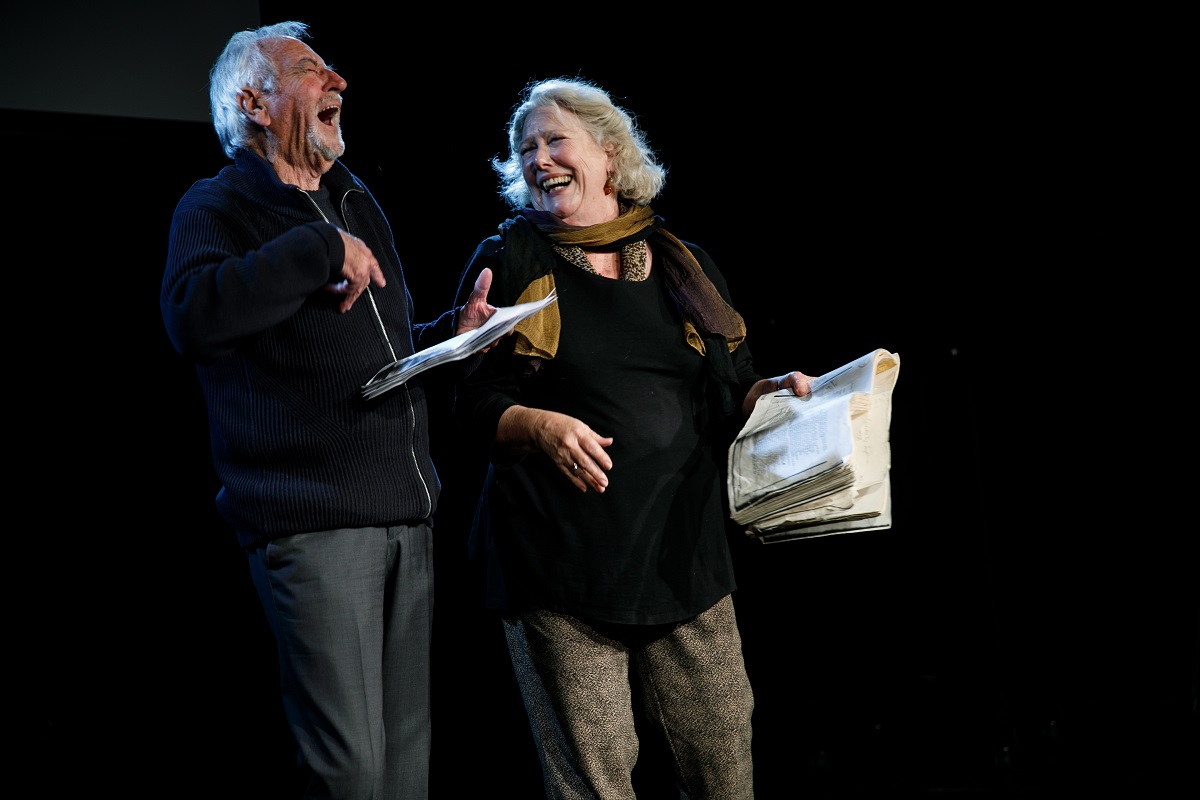

Wilson took me through the essential features of the exhibition, which includes more than 180 drawings, steel and wood-engraved illustrations and paintings by artists dispatched across Australia and the Pacific, and, most fascinating to me, the original engraving tools of “Atlas” artist George Collingridge.

Wilson’s co-curator, Gary Werskey from Sydney University, is the author of “Picturing a Nation: The Art and Life of A.H. Fullwood” and they have anchored the exhibition family in the bohemian art scene of late 19th century Sydney, particularly attractive to AGNSW, since the reputation of Sydney giants like Julian Ashton, Albert Henry Fullwood and Frank Mahony were to be eclipsed by that of the Heidelberg school in Melbourne.

As Wilson notes philosophically, “history is written by the victors” and they were no match for a self-promoter like Melbourne’s Arthur Streeton.

While the art of Fullwood and Mahony is still widely known, Ashton has gone into the annals less as an artist than as the founder of the Julian Ashton Art School in Sydney and a trustee of the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

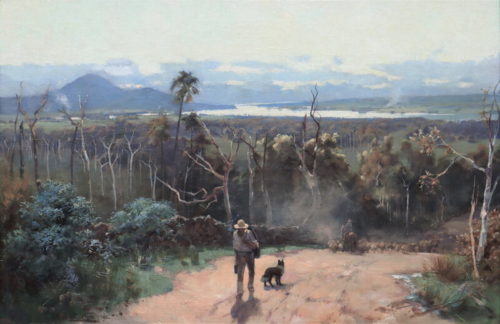

But this exhibition does show Ashton’s “The Prospector” and his famous picture of Ned Kelly in the dock.

Artworks are also on show by other “Atlas” contributors, William Macleod, Ellis Rowan, Constance Roth and Americans and Frederic B. Schell and William Smedley, whose impressionistic, rain-washed streetscapes Wilson particularly admires.

In fact, it is the contention of Werskey and Wilson, highlighted in the final room of this exhibition, that “The Picturesque Atlas”, which documented life in the still-colonial Australia through illustrations, maps and text, served as a catalyst for the Australian Impressionism art movement that followed.

From the art history perspective, the exhibition is a must-see, with much evidence of the “en plein air” approach to painting advocated by Ashton, the rare presence of female artists like Rowan and Roth, the emerging technology of photography and the technique of transferring photographic images onto wood blocks for engraving.

The differences between the “Atlas” artists emerge clearly in the show. Macleod and Mahony worked at “The Bulletin”, so became adept illustrators of works by Henry Lawson and Banjo Paterson, but when left to their own devices, Macleod preferred portraiture, Mahony liked painting animals and Ashton went for miners and selectors.

Sydney’s “Atlas” artists, Wilson surmises, enjoyed “a roaring time” and enjoyed collegiate relationships between artists of the time, including the visiting Americans who, oddly, called themselves “the kangaroos”. They also went on tours such as Fullwood’s excursion to the Hunter Valley, well documented in the show.

Central to the exhibition is the art of engraving.

During this era, the art of halftone printing was not yet developed and so it was necessary to prepare works for printing through engraving, raising the age-old question of where art ends and craft begins, since in some cases by eliminating extraneous detail and enhancing the skies through cross-hatching and other fine line techniques, the engravers sometimes improved on the originals.

The world of 19th century illustrations may give what Wilson calls a “biased” or partial view of Australian life but visually, it is an accurate one.

“A Nation Imagined: The Artists of the Picturesque Atlas”, National Library of Australia, until July 11, 9am to 5pm daily. Entry is free.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply