JON STANHOPE and KHALID AHMED are concerned at the bureaucratic mocking of people seeking care at an emergency department because of a subjective assessment that their condition is ‘mundane’, but it all comes down to underfunding.

AMIDST a sharp increase in covid-related hospitalisations in Canberra, and mounting pressure on emergency departments, the chief operating officer of Canberra Health Services, Cathie O’Neill, has reportedly identified a range of “mundane reasons” people are seeking emergency care.

Some such reasons included, for example, blocked ears and constipation. O’Neill is reported to have said that people needed to consider how serious their health concern really was before deciding to attend the emergency department.

O’Neill does not appear to have provided advice on the number of such presentations. For example, it is unclear what proportion of overall presentations the “mundane” issues constituted or the extent to which such presentations impacted on the operations of the emergency department.

Notably the Productivity Commission “Report on Government Services” reveals that the proportion of Category 4 and 5 (semi-urgent and non-urgent) presentations at Canberra hospitals decreased from 57 per cent in 2014-15 to 46 per cent in 2020-21, and are lower than the national average of 47 per cent and 51 per cent in NSW.

Non-urgent presentations (Category 5) have also similarly remained below the national average and presentations in NSW hospitals.

We acknowledge, of course, the pressure on the hospital system that originated, of course, in the years of underfunding before the pandemic, but have been exacerbated by recent waves of infections in the general population as well as staff.

It is entirely reasonable for health officials to inform the community of these pressures, and to ask for our understanding of the challenges faced by staff.

It is also reasonable to advise the community of the various other channels of service which could be reasonably accessed, for example, walk-in centres, after-hours locum services or phone hotlines. However, it’s concerning that mocking people seeking care and dissuading them from presenting at an emergency department because of a subjective assessment that their condition is “mundane” is not only disrespectful but could have serious consequences in some cases.

“Surely, people should not be expected to self-assess or self-diagnose or avoid presenting themselves at a public health facility for a proper clinical assessment.

While the medical merits of the “mundane” condition are best left to clinicians to determine, from the perspective of an ordinary citizen, constipation may be a symptom or even description of (say) intestinal obstruction or bowel blockage. Likewise, blocked ears may be due to an infection, the seriousness of which can only be determined by a qualified clinician.

The point is, surely those with such symptoms should not be expected to self-assess or self-diagnose or avoid presenting themselves at a public health facility for a proper clinical assessment. The consequences of ignoring mild or mundane symptoms can sometimes be severe.

While, thankfully, extreme adverse events in such circumstances are rare in Australia, they do occur to the enduring pain of the families and clinicians involved. A further problem with this “mundane symptom framework” is that it begs the question: where should it stop? Should someone concerned with pain in the arm or disorientation, albeit mild, consider it mundane and ignore it or seek a medical opinion.

From the viewpoint of emergency response systems, every presentation and every call should be taken seriously until assessed otherwise.

As an example, typically, less than half of fire brigade callouts relate to an actual incident, and roughly one third of those will be characterised as being serious. It would, nevertheless, be unthinkable to suggest that the responsiveness of the system should be reduced. An increase in response times, whether for fire brigade or ambulance, does not warrant asking people not to call, but rather an appropriate policy response, namely an increase in response capacity.

Yet, that is what the Minister for Health, Rachel Stephen-Smith appears to have argued when she reportedly said in the context of current pressures on the health system: “[We] know that expanding the size of emergency departments often actually encourages more people to come to emergency departments.”

“The minister’s emergency department comment suggests a concerning misunderstanding of the consequences of relentless underfunding of health services and infrastructure.

While the minister’s comment could have been lifted from the script of an episode of “Yes, Minister”, it suggests a deeply concerning misunderstanding of her role and of the consequences for Canberrans and frontline clinicians of relentless underfunding of health services and infrastructure.

Media reporting of this issue referred to a study from the University of Wollongong that found elderly patients often presented at emergency departments unnecessarily because they misjudged the severity of their condition. Ex post analyses of diagnosis and patient categorisation are useful in developing alternative pathways and refining triage processes within an emergency department. However, they should not be used or invoked to tell people who feel they need help not to seek it.

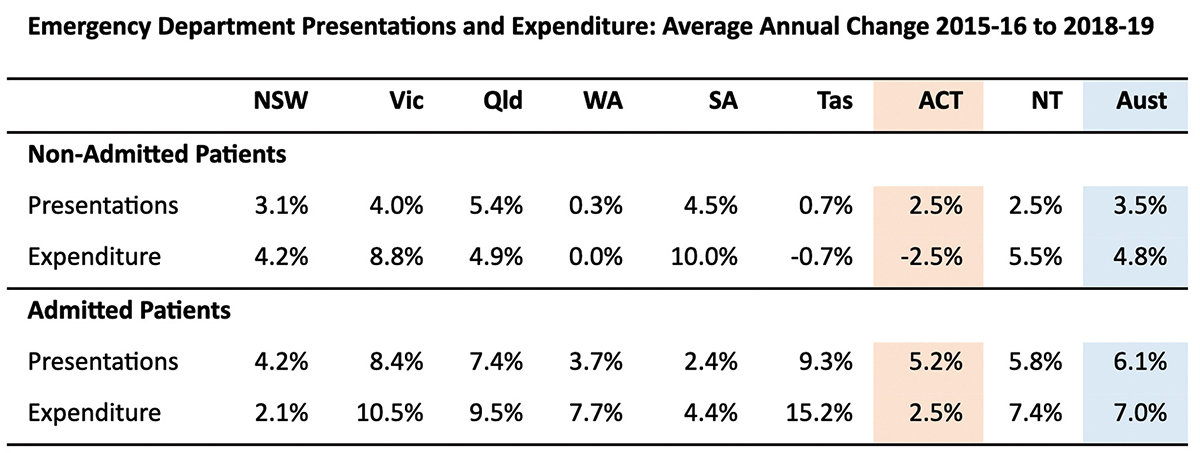

The table illustrates the average annual change in emergency department presentations and expenditure over the period 2015-16 to 2018-19. The data for 2019-20 has not been included in order to examine the growth in demand and the expenditure allocated across states and territories before the pandemic.

Source: Report on Government Services; Productivity Commission (2022).

In the lead up to the pandemic, presentations that did not end up in admission increased at an average rate of 2.5 per cent per annum, while the expenditure was cut at a compounding rate of 2.5 per cent annually. Nationally, such presentations grew at 3.5 per cent per annum, and expenditure growth was 4.8 per cent per annum.

For presentations ending in admission, the average annual growth was 5.2 per cent (6.1 per cent nationally), and expenditure growth was 2.5 per cent (7 per cent nationally). Only NSW had lower expenditure growth, however, its demand was also relatively lower.

These figures reflect the minister’s thinking on and response to emergency department funding, and explain the pressures that frontline clinicians in Canberra hospitals have endured before and during the pandemic. To be blunt, they have been starved of funding.

Jon Stanhope is a former chief minister of the ACT and Dr Khalid Ahmed a former senior ACT Treasury official.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply