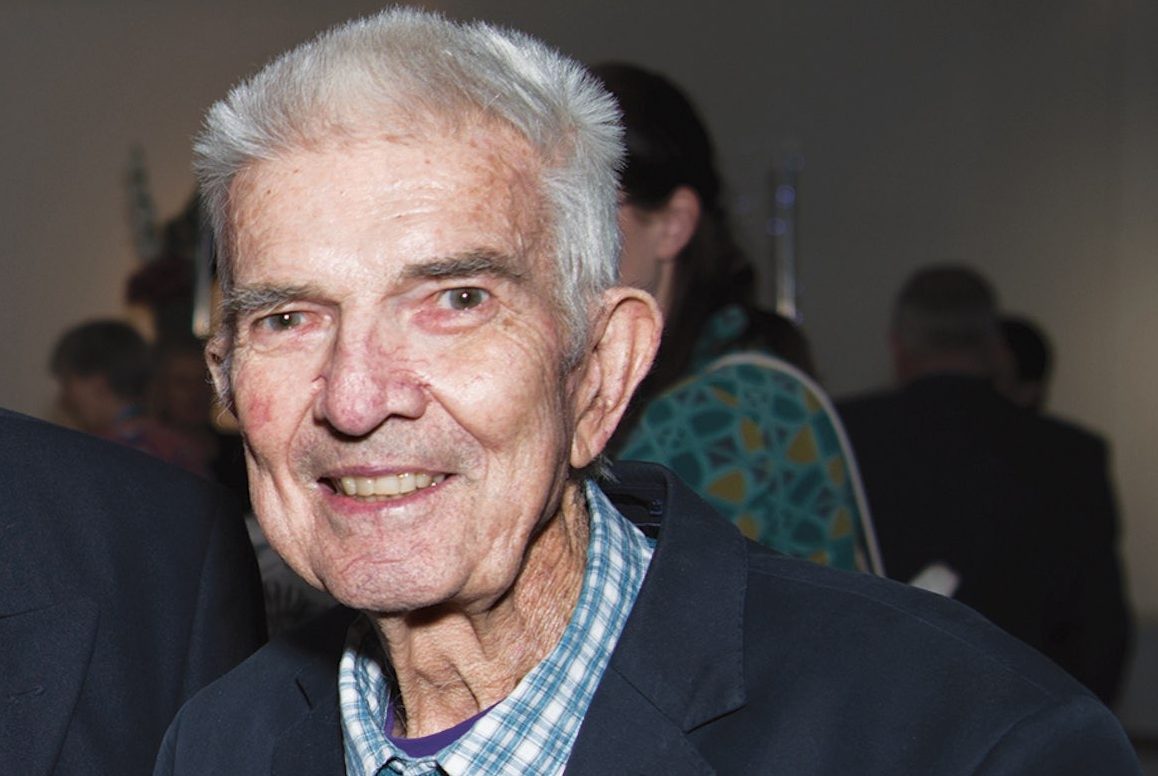

FORMER University of Canberra vice-chancellor Don Aitkin died in Canberra this morning (April 12) He was 84.

He served as UC vice-chancellor from 1991 to 2002.

Aitkin was a political scientist, writer and administrator.

On his website last year, in an essay titled “On Death and Dying” (and published in full below) he wrote: “When you die, that’s it. Do I fear it? No, not really. I have had a wonderful life, and I have no bucket list.”

Until 2012 he was chairman of the National Capital Authority and was vice-president of the Australian Vice-Chancellors Committee in 1994 and 1995.

He played an influential role in the evolution of national policies for research and higher education from the mid-1980s, when he was the Chairman of the Australian Research Grants Committee, a member of the Australian Science and Technology Council, and Chairman of the Board of the Institute of Advanced Studies at the ANU.

He was the first chairman of the Australian Research Council in 1988, he established the new body as a national research council of world class; its funding trebled during his term of office.

Don was also an occasional columnist in “CityNews”.

A skilled piano player, he is remembered locally for his long and loyal service as chair of the Canberra International Music Festival during its formative years.

He was appointed an Officer of the Order of Australia in 1998.

In an essay on his website in June last year, titled “On Death and Dying”, he wrote:

“I live in an aged-care facility, commonly referred to as ‘God’s waiting room’. I’ve been there now for two and a half years, and am the longest-serving resident at my table. The others are all men. Six guys have died from that table in my time, and one was moved into ‘high care’ because he was disruptive.

“We don’t talk about death or dying much, only to say, in rather hushed voices, that ‘so and so’ has gone. If it is someone close to us we will line up at the front door when the body is taken away, and I’ll sing ‘Goodbye, goodbye, we’re wishing you a fond goodbye…’

Family members are sometimes surprised at this. I think they don’t realise that in our facility new friendships are forged, often quite quickly. My closest friend here is Max, who is a little older than me and was born in Serbia. He and I have similar medical problems. He has done a number of things since coming to Australia, most notably as a gas fitter. He is a big jovial man, notably good-humoured, with a lovely chuckle. He and I wonder from time to time when we will go.

For the wheels are coming off our carts, Max’s and mine. Just as one thing gets fixed, in a sort of way, along comes another, and we have to endure that. My cancer and its associated chemotherapy make me tired, and I sleep a lot. Max gets at most three hours sleep a night. He envies me. Some of our residents never come to the table, and we don’t know them at all. When they die, we don’t actually know who they were.

I’ll be 84 in a few weeks, and would like to at least get to 88, the age at which my mother died. Dad died a few months before attaining 88. My grandparents got to around that age as well, so it is a good family mark.

When we look at some of our residents, who have dementia or acute osteoporosis or some other unpleasant condition we say quietly to one another, ‘I don’t want to finish up like that’. But those with these conditions seem to be hanging on to life. There comes a time, in my case three or four years ago, when you realise that you really are going to die. Before that moment, death is something way ahead. Suddenly it’s not, any more, and you need to think about the consequences for your family. ‘Get your affairs in order’ is the command of the surgeon who sewed the patient up, shaking his head at the impossibility of dealing with whatever it is that will take him away.

What happens when you die? I watched my lovely wife die, and I was holding her hand at the time. She had erratic breathing, and then it just stopped. Like that. She had gone from us. I am not a believing Christian, and I envy the few I know who are. In fact I’m only a Christian in the sense that our culture has a powerful element of Christianity embedded in it, and to have imbibed it from childhood was simply inescapable. I am agnostic about God and Heaven and Hell, not an atheist.

To be an atheist would require much more intellectual effort than I have ever been prepared to put in. I was told at Sunday School that I needed to believe in Jesus, but I didn’t know what that meant. What did ‘believe’ mean? I’m not sorry that I had the Sunday School experience. It was part of growing up and learning. But I waited for God to speak to me, perhaps like St Paul. He (she) never did, and I gave it up.

So my expectation is that I will cease to exist other than in the minds of those who knew me. All being well I will not be in pain, and will just fade away. A sudden heart attack would be a preferred end, and even better, falling asleep and never waking up. But I don’t expect some sort of continuation.

When you die, that’s it. Do I fear it? No, not really. I have had a wonderful life, and I have no bucket list. I go on writing novels because I enjoy the use of my creative powers in that way. I play the piano occasionally. I’m still able to drive, and I see some of my children regularly, and correspond with them all. I talk to my friends at the dining table. One day something will cause more wheels to fall off. At this moment that something seems far away. But I know very well that it could come tomorrow. My response is a sort of mental shrug.

So I will help my eldest son design my funeral service, about which I do have experience. He has my EPOA (enduring power of attorney), and he is sensible, far-sighted and caring. I hope it’s a good funeral service, and there is no Covid or similar problem when I do go to prevent friends and rellies from attending.

There’s not much I can add. Death is inevitable. It is not pleasant, especially to the friends and rellies of the one dying. I have no objection to euthanasia, though its use requires safeguards. Would I use it myself? Yes, if the pain were unendurable, though these days pain can be managed. I would want to talk about it to my nearest and dearest before I did anything. I might ask my doctor to slightly overdose the morphine, and I would slip quietly away. I should quickly add that I doubt that any of my doctors would agree to this procedure.

Some of our views change over time. I was once opposed to nuclear power. I now think it is a useful adjunct means for those who worry about greenhouse gas emissions, though I’m not one of those. Coal will do for me. In similar fashion I was once opposed to voluntary euthanasia, but now I see it as a means of ending a life that no longer has purpose or any joy. To repeat, it needs safeguards, but they are available. When my turn comes I hope I will face the end bravely and serenely. I see no reason to suppose otherwise.”

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply