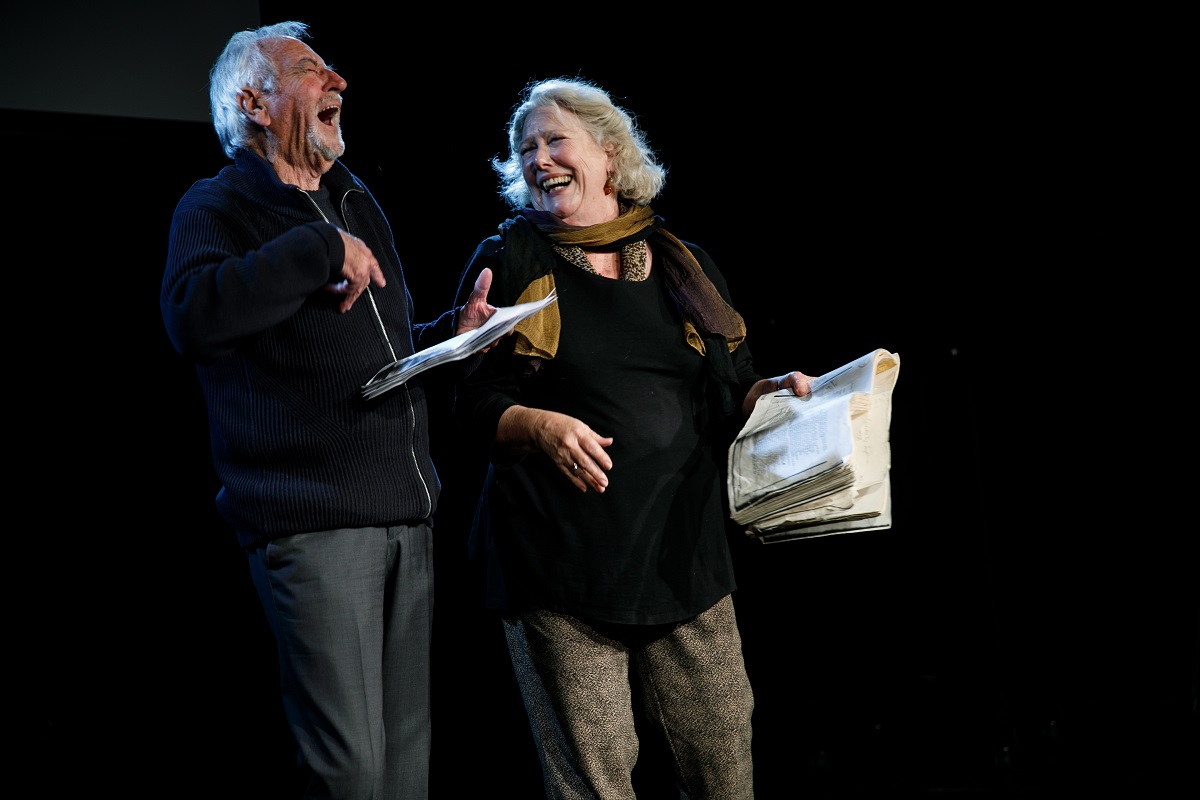

Arts editor HELEN MUSA reviews former director John Clark’s book on the rise and fall of NIDA.

JOHN Clark’s book, “An Eye For Talent: A Life at NIDA”, will have cavalcades of artists who’ve passed through the doors of the National Institute of Dramatic Art rushing to the index to see whether they’re in it, but they might be disappointed.

For the book is as much about the decline and fall of a great institution as it is about the stars.

Clark, the third director of the institute from 1969 to his retirement in 2008, is as well-positioned as anybody to look back on the evolution of a drama school that started as a very small enterprise and went on to become one of the leading theatre training schools in the world.

The readable opening section traces the background to NIDA and the nurturing role played by the “eminence gris” of the theatre and first director of NIDA, Prof Robert Quentin; English theatre director, Hugh Hunt; founding chair HC “Nugget” Coombs; Melbourne director John Sumner; director Tom Brown, and the vice chancellor of the University of NSW, Sir Philip Baxter, whose wife liked to make hats for the theatre.

With a shared vision of NIDA as a place to “do” rather than to analyse, the mix of personalities and ideas combined to make up the triple-headed theatre model of training school, academic drama department and professional theatre that probably had its origins in Bristol, England.

After a short theatrical prologue, the book opens with Clark’s origins in Hobart where, following a notorious stint in student politics, he fell into theatre and received an offer to study at Bristol University’s drama school, the first such school in England and closely associated with Old Vic theatre School. Despite a happy time there, Clark frequently stresses the “doing” part of theatre, taking occasional sideswipes at academics.

He traces the beginnings of NIDA from 1959, when he joined the staff as a junior theatre history teacher, as the fledgling drama school found a home in a tin shed, an old two-storey racecourse jockeys’ changing room, and the old Kensington racecourse totaliser opposite Randwick Racecourse, which would give its name to the Old Tote Theatre.

Right from the start, a galaxy of stars passed through the doors and Clark rejoices in dropping names such as Robyn Nevin, Jim Sharman, Hugo Weaving, Mel Gibson, Judy Davis and Baz Luhrmann and much later Cate Blanchett.

To him, the acting course was pre-eminent and while he sometimes pays attention to the technical production and design courses, these are subsidiary.

Equally valuable is the section where Clark describes the manoeuvrings to squeeze money out of Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser for a new suite of buildings on Anzac Parade, Kensington, which followed the near-decision to relocate NIDA to the Seymour Centre. Here Clark places bursar and later general manager, Elizabeth Butcher at the centre of the narrative.

Butcher, the “girl from Gundagai” whom Clark appointed because she didn’t know anything about theatre, was to become one of the most powerful theatrical forces in the land – she and Clark even managed the very first season of the Sydney Theatre Company after the collapse of the Old Tote Theatre.

Theatre people will enjoy his account of the NIDA personalities and productions, a who’s who of the Australia theatre, of gruelling NIDA auditioning tours and “exit” auditions, along with his personal recollections of the gradual opening to First Nations actors, the founding of Jane St Theatre and the Open Program and the evolution of a directing course.

Success followed. By 1999, when Hansard recorded the Australian Senate as congratulating NIDA, there was a new building and, he reports, “a system of theatre training based on a clear philosophy that informs both teaching and play productions.” By 2001, there were 2000 applicants annually for places at the institute.

But naturally, along with several “golden” ages, there were periods of foment and discord. Here Clark’s approach is to quote from the favourable criticisms of his own shows and eliminate key detractors from the story altogether .

An exception is a series of incidents in the 1990s where a triumvirate of board members attempted reform. Regrettably, he misspells the name of the male antagonist in the story.

He also expresses regrets so that neither Richard Wherrett nor Robyn Nevin, once at Sydney Theatre Company, took much interest in NIDA, breaking a nexus that had existed since the early days.

Clark is an affable raconteur with a lively, yarning style, but I rather wish he hadn’t resorted to the editorial tactic of breaking up the narrative with Shakespearean quotations, sometimes apposite, but more often giving it a slightly twee, 19th century flavour.

As well, the frequent inaccuracies, the telescoping of separate events and the omission of well-known heads of NIDA course makes it a partial account.

But all’s well that ends well. Clark may not be best placed to describe his own misadventures, but his political savvy and ability to mount a strong argument come to the fore in the last part of the book, something that editor Nicholas Parsons writes he hopes will serve to guide a later administration in remaking NIDA “yet again”.

Clark gives no quarter as he names the names and lays into the increasing corporatisation of NIDA, the irresponsible sacking of staff and replacement of them with people of limited theatrical experience and, most of all, the decision to place all power in the hands of a director/CEO instead of practising the separation of talents that gave the Clark-Butcher team its longevity.

The book, like a play, has its prologue and an exposition, its crises, its climaxes, and its sad denouement.

The final chapters of “An Eye For Talent” are a salutary reminder that it is so much easier to destroy an arts institution than to create one.

“An Eye For Talent: A Life at NIDA” by John Clark, Coach House Books, RRP $40.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply