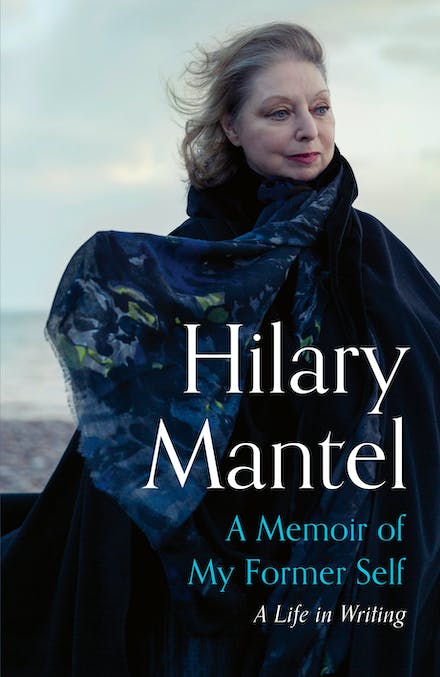

COLIN STEELE reviews a collection of essays by the late Hilary Mantel, ‘one of Britain’s greatest contemporary writers’.

A Memoir of My Former Self, a posthumous collection of four decades of Hilary Mantel’s writings, edited by Nicholas Pearson, her book editor for more than two decades, has been publicised as “a celebration of one of Britain’s greatest contemporary writers”.

Mantel died, at the peak of her creative powers, aged 70, on September 22, 2022 following a stroke.

Mantel’s career and material success can be divided into two chronological sections, before and after her Thomas Cromwell trilogy, Wolf Hall (2009), Bring Up the Bodies (2012) and The Mirror and the Light (2020), the first two of which won the Booker Prize. The trilogy has sold more than five million copies worldwide and been translated into 41 languages.

Mantel wrote 17 books in total. A Memoir of My Former Self , brings together 71 pieces written between 1987 and 2018 for journals and newspapers, such as The Guardian, the New York Review of Books and The London Review of Books.

Mantel wrote in 1987: “I have no critical training whatsoever so I am forced to be more brisk and breezy than scholarly”, which ensures the continuing readability of the essays, which cover a wide range of topics, from historical figures, such as Henry VIII, Robespierre and Marie Antoinette, to commentary on nationalism, feminism, identity, literature, art and religion.

In her essay on the Irish writer John McGahern she notes that religion is, for some, “protection against deeper thought”.

Several of her public lectures are included in the collection, notably her 2017 Reith lectures in which Mantel considers the nature of the past, arguing historical fiction is the partner of historical “fact”.

She believed that her role as a novelist was “not to be an inferior sort of historian but… to deepen the reader’s experience through feeling”.

Several essays cover Mantel’s complex childhood, family trauma, marriage and her health, which was covered in more detail in her 2003 memoir Giving Up the Ghost.

Mantel, as a young woman, suffered from an initially undiagnosed condition of endometriosis. Male doctors told her she was neurotic, her pain simply induced by hysteria and depression.

Mantel, who underwent a hysterectomy at 25 endured lifelong physical and psychological stress from the illness and became as she puts it, “an unwilling stranger in my body”. Mantel writes that today, “women’s health isn’t trashed so casually… The women of any family have history written on their bodies. Mostly it’s a story of progress. But our story stops with me”.

Not surprisingly, Montel’s feminist viewpoints permeate a number of essays. Her anger at the subservient role of females in Saudi Arabia, “It is apartheid: stringent, absolute”, based on her time living in the country, comes through strongly in the essay, Last Morning in Al Hamra.

Mantel’s 2013 London Review of Books lecture, Royal Bodies, is surprisingly not included in this collection, but it is available in her LRB collection Mantel Pieces (2020). It caused a media furore when she described Kate Middleton inter alia as “a shop-window mannequin, with no personality of her own, entirely defined by what she wore”, framing Kate for a commentary on the commodification of Royal women.

Her essay, The Princess Myth, on the fall and posthumous rise of Diana in the public imagination, exemplifies Mantel’s focus on how the dead live in memory, how power is exercised and the place of women in society.

Mantel was a great admirer of Jane Austen. At the time of her death, Mantel had been working on a “mashup” of Jane Austen novels, focusing on Mary Bennett, the least prominent sister in Pride and Prejudice.

Readers unfortunately will now never read that but have to make do with Mantel’s long 1998 essay on Austen, in which she reflects that “Austen defies cheap psychology and trite formulation. The contradictions in her life and work are fertile”.

Her long essays on female writers, such as Elizabeth Jane Howard, Annie Proulx and Rebecca West show Mantel at her most incisive. On West she comments: “It’s her vices, as much as her virtues, that make her letters so compelling” and sympathises with Elizabeth Jane Howard: “The real reason [her] books are underestimated – let’s be blunt – is that they are by a woman”, noting how Howard had to play second fiddle to Kingsley Amis in their marriage.

Mantel’s social conscience is throughout fortified with an independence, at times contrariness, which permeate the essays to reveal a fearless self-portrait, in her own words, delivering “messages from people I used to be”.

A Memoir of My Former Self: A Life in Writing by Hilary Mantel. Selected and edited by Nicolas Pearson. John Murray. $34.99.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply