“Many university libraries, including in Australia, have, in recent years, deaccessioned hundreds of thousands of physical books on the premise that digital copies are available,” laments COLIN STEELE in his review of The Book at War.

Andrew Pettegree, professor of modern history at the University of St Andrews reveals in The Book at War how “print in all its manifestations”, which includes books, newspapers, scientific papers, maps, letters, diaries and leaflets, has shaped the course of war throughout history.

The book explores the weaponisation of book culture under six main headings: building a fighting nation; libraries as munitions of war; books on the homefront; providing books for troops: book plunder and destruction in wartime; reconstruction of book stocks and the war for ideological supremacy in the Cold War.

Pettegree demonstrates that, throughout history, the content of books can be used for good or evil. They can stimulate patriotism but also spread misinformation as “vectors of poisonous ideologies”.

Pettegree asks: “Was the bombing of libraries, the destruction of books, always a tragedy… Should we lament the loss of the nine million copies of Hitler’s Mein Kampf circulating in Germany by 1945, or the 100 million copies of Mao’s Little Red Book destroyed when his cult receded?”

In that context, while the Nazi book burnings of the 1930s are to be absolutely abhorred, we forget that significant numbers of German books were burnt in America during World War I.

Books have always been trophies or victims of war. Pettegree, in the first chapter, references the Roman general Sulla “parading through Rome with Aristotle’s library as a looted spoil of war”. The Spanish deliberately destroyed the records of the Aztecs and Mayan civilisations and propagated Catholic texts, while in the 17th century Swedish forces ransacked the libraries of central Europe in order to stock Swedish libraries and to limit the spread of Catholic texts.

During World War II, Poland lost 90 per cent of the contents of its public and school libraries and in 1992 Serbian troops deliberately targeted the National and University Library of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Destroying libraries has over the centuries been seen as “a thrust at the heart of an enemy society”. Pettegree ironically notes the major wars of the 19th and 20th centuries were “fought between the world’s most bookish nations”.

Throughout history, books have provided military strategic frameworks, Pettegree highlights Sun Tzu’s sixth century BCE classic The Art of War; Machiavelli’s similarly titled The Art of War (1521) and Carl von Clausewitz’s On War (1832). Other publications were either implicitly or explicitly intended for influencing a particular cause.

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, for example, proved influential in shaping Union support for the Civil War. George Orwell’s Animal Farm was especially popular in the Cold War. Pettegree reflects that the best works of propaganda were never originally intended as such.

Books can also provide relief in times of war. Anne Frank, hiding from the Germans in Amsterdam during World War II, found solace in books, while library associations and publishers provided books to frontline troops, particularly notable were the US Armed Services small paperbacks. In total, 122 million copies of more than 1300 titles were delivered to armed forces personnel. The accessibility of print and the low unit cost of books proved essential in war.

In a different kind of war, we see libraries today, especially in America, under threat from groups such as creationists and school library “parents’ rights” groups seeking to remove or destroy books, thereby restricting free speech and attacking democracy.

Pettegree, while recognising “the domination of new technologies of war-making and information gathering”, as reflected in the Russia-Ukraine war, does not go into detail in this respect.

When the internet goes down so does society. The major cyber attack in late October 2023 on the British Library in London represents a different kind of war on the book and its digital fragility. The ransom attack on the British Library totally dismantled access to the library’s electronic infrastructure databases and digital content.

The British Library was effectively “technologically immobilised” with rebuilding the database and new cyber defences expected to take up to 12 months and cost between six and seven million pounds.

Pettegree’s concluding remarks on the continued importance of the printed book resonate here. Many university libraries, including in Australia, have, in recent years, deaccessioned hundreds of thousands of physical books on the premise that digital copies are available. Pettegree sums up “the library is far from dead, and its contents will continue to be a subject of social and political importance”.

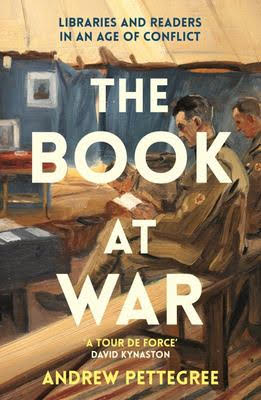

The Book at War: Libraries and Readers in an Age of Conflict by Andrew Pettegree. Profile Books. Rrp: $55.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply