Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that the following article may contain images and voices of people who have died.

FOR many January 26 is a day of celebration, one of barbecues, beaches, fireworks and waving the Australian flag with pride.

For others, it’s a reminder of the dispossession and marginalisation of indigenous Australians whose heritage stretches back more than 60,000 years.

The contention around Australia Day grows with each passing year and now, more than ever, it’s important to ask the question, what is the history of Australia Day and does it have a future?

January 26 itself marks the day that Capt Arthur Phillip, commander of the First Fleet of 11 convict ships and the first governor of NSW, set foot on Sydney Cove in 1788 and raised the Union Jack to signal the beginning of the new colony.

By the early 1800s, almanacs, calendars and the “Sydney Gazette” referred to the date as “Landing Day” or “Foundation Day” and Sydney dwellers would drink, dine and dance in celebration of the quickly growing nation.

These festivities were especially enjoyed by emancipists – convicts who served out their sentence or received a pardon and who would rejoice in their freedom.

By its 30th anniversary in 1818 the celebration of “Foundation Day” had become widespread enough for the then NSW governor Lachlan Macquarie to declare it a public holiday.

It was not long after Capt Matthew Flinders, who had circumnavigated the continent, suggested the land be named Australia, derived from “australis”, which means “southern” in Latin.

The country was beginning to emerge, and while the celebration of its founding had become prolific throughout NSW, it wouldn’t be until a century later that a more matured nation would commemorate it nationally.

In 1888, representatives from Tasmania, Victoria, Queensland, WA, SA and NZ joined NSW leaders in Sydney to celebrate 100 years since the flag was first raised on Australian shores.

Not long after, in 1901 the colonies of Australia would federate to become the Commonwealth of Australia, with Canberra named its capital in 1913.

By 1935, the term “Australia Day” was used throughout the country to celebrate its history, except in NSW where it would remain “Anniversary Day” for a little longer.

But while the nation had grown quickly in a century, so too had the anger at the injustice brought on the Aboriginal people by colonisation that’s still felt today.

In the decades following the arrival of European settlers, tens of thousands of indigenous people lost their lives due to diseases brought from the foreign continent and from the resulting colonial violence and conflict.

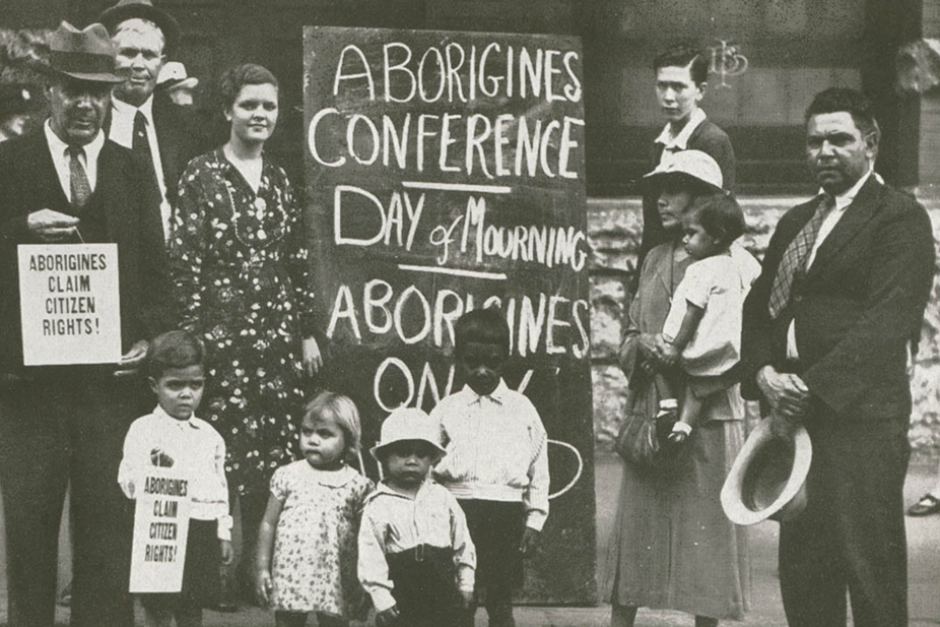

In 1938, which marked Australia Day’s 150th anniversary, indigenous leaders met in Sydney and declared it a day of mourning, one where they protested the mistreatment of their people and sought full citizen rights.

While for some time the indigenous community had been lobbying to protest, 1938 represented the first occasion that activists from different states had fully co-operated.

“This is not a matter of race, this is a matter of education and opportunity,” said protest organiser and journalist Jack Patten on the historic day.

“This is why we ask for a better education and better opportunity for our people,” he said.

“We ask for ordinary citizen rights, and full equality with white Australians.”

As Australia Day rolled around each year, both celebrations of the event and protests widely inspired by Patten’s advocacy continued to become more abundant.

By 1984, new Australian citizens were no longer considered British subjects, the same year that “Advance Australia Fair” was finally decided as the national anthem in favour of “God Save the Queen”.

Four years later, on the 200th anniversary of Capt Phillip’s arrival at Sydney Cove, parades were held around the country while 40,000 Aboriginal people and non-indigenous supporters marched through the streets of Sydney and renamed January 26 “Invasion Day”.

The public holiday today remains an important date to many Australians for very different reasons. According to the National Australia Day Council, four out of five people see it as “more than a day off”, especially meaningful for the thousands of new citizens who are officially welcomed to the country.

Is there a future for Australia Day though especially with the growing “Change The Date” movement?

CEO of the National Australia Day Council Karlie Brand says it’s important we reflect on our nation’s history and learn from it, celebrate our ancient history and be optimistic about our future.

“We’re all part of the story of Australia – from those whose ancestors walked on country for tens of thousands of years to those who came in the waves of migration that followed on to our newest citizens,” says Ms Brand.

“On Australia Day, we celebrate being part of a proud, ancient, multicultural nation that values the contribution of each and every citizen.”

It seems that, for the foreseeable future, Australia Day will continue to be celebrated on January 26. Whether or not one agrees or disagrees with the commemoration of the date, there is pride to be taken in the fact that this country provides people the opportunity to converse, to protest, to argue and to reflect on the course of its history and have a voice in its future.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply