“In the 2020-21 Budget, prepared with knowledge of the increase in demand for services and delivered at the height of the covid pandemic, the mental health budget suffered an actual cut in funding of $300,000,” writes columnist JON STANHOPE.

IT was challenging to read, in “The Weekend Australian”, details of the impact which the extended covid lockdown in Victoria has had on the mental health of young people.

The paper referenced a report it says was prepared for the information of the Victorian government, which reveals that more than 340 teenagers a week have been admitted to hospital suffering mental health emergencies in Victoria.

The six-week average to May 30 this year represents a 57 per cent increase on the corresponding period last year.

Even more concerning, it reported that, in the same period, an average of 156 teenagers a week were admitted to hospital after self-harming and/or suffering suicidal thoughts, an 88 per cent increase on last year.

While acknowledging that Victoria has a much larger population than the ACT and has been in lockdown for a vastly greater period, the issues raised by the Victorian experience surely demand an immediate and serious respons here in Canberra and across Australia.

The threshold issue is, of course, our state of preparedness and capacity to respond to a surge in mental health issues of not just the order experienced in Victoria but an increase in demand of any magnitude.

A first step in understanding the capacity of mental health services in the ACT to be able to respond to a covid-related surge in mental health problems, including but not restricted just to young people, would be to have a look at the funding dedicated to mental health in the last (say) four ACT Budgets.

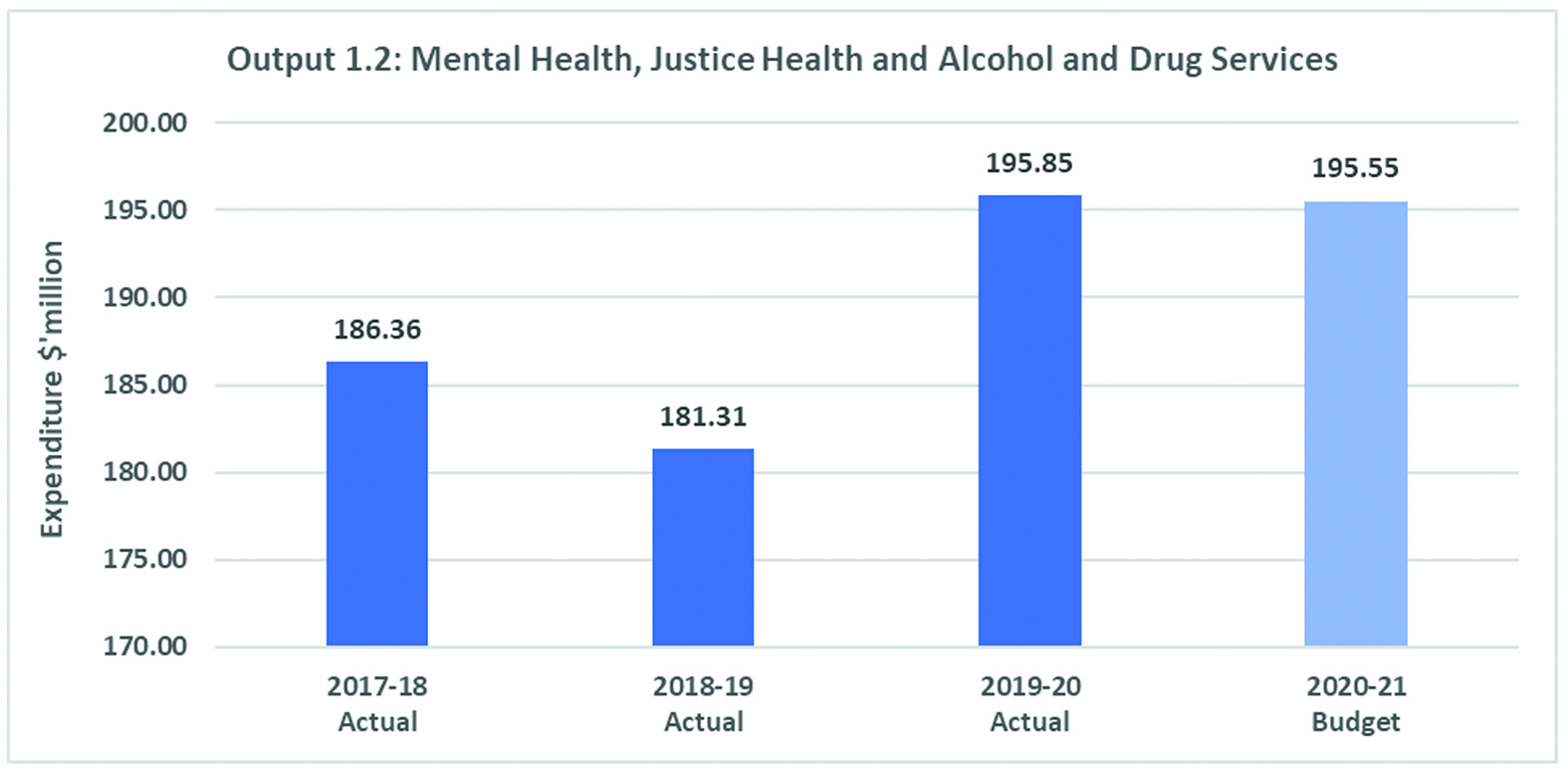

A quick look reveals, as illustrated in the chart below, a decrease in mental health funding of just on $5 million between 2017-18 and 2018-19 followed by an increase of $14 million in 2019-20 (which notes in the annual report indicate was covid related) but then a reduction in the 2020-21 Budget of $300,000.

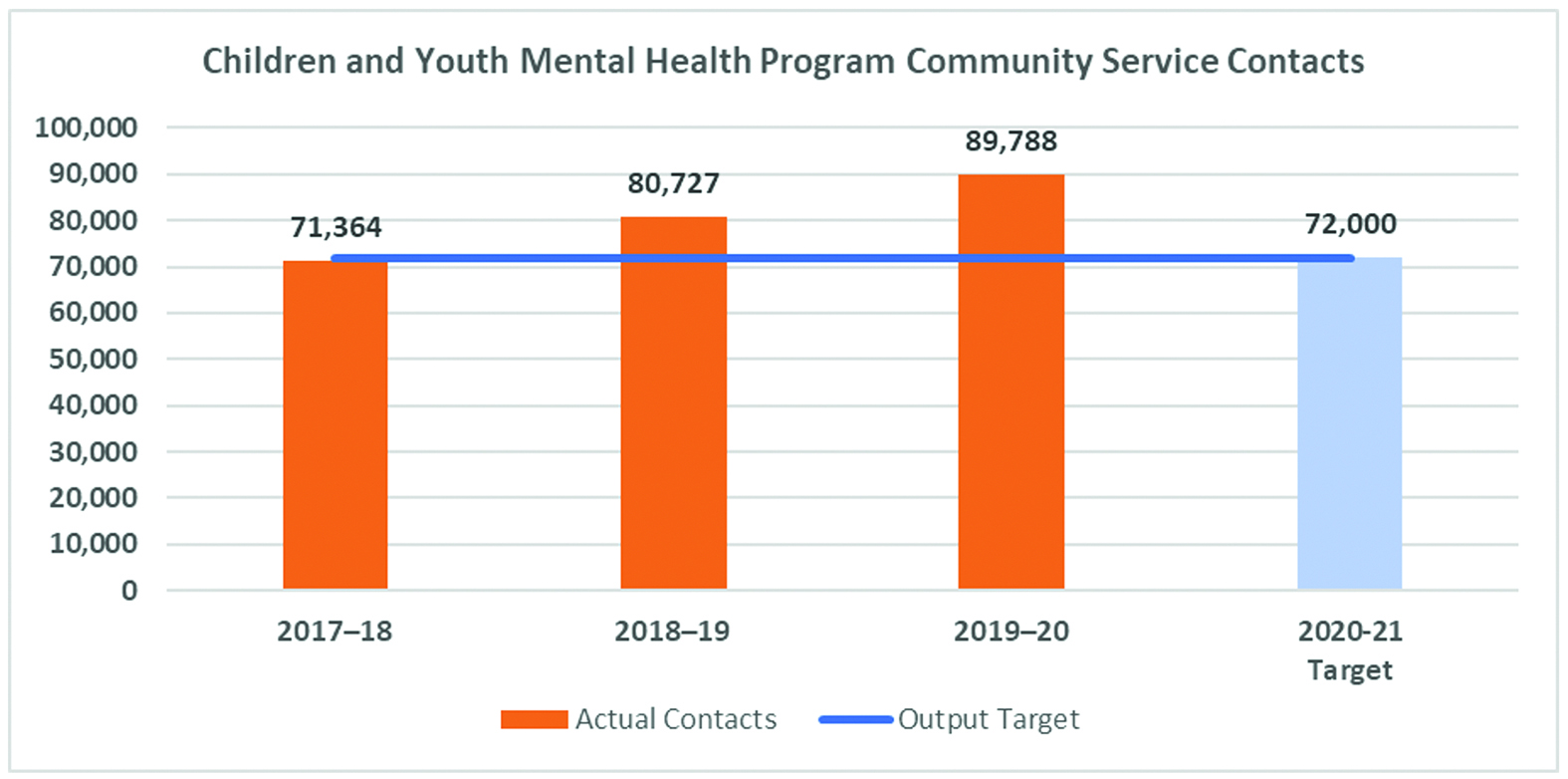

It is also notable that the output or activity target across the four years, for each of the mental health sub-categories, has remained the same despite the changes in the annual appropriation for mental health.

The ACT Health annual reports reveal, as illustrated for example in the following charts, that despite the number of actual community service contacts in 2019-20 under the Adult Mental Health Program being 212,794, an increase of 13 per cent on 2018-19 and 14,794 more than the target of 198,000, which presumably was the number against which funding was calculated, the target of 198,000 was nevertheless retained for 2020-21.

In similar vein, the actual number of community service contacts under the Children and Youth Mental Health Program in 2019-20 was 89,788, an increase of 11 per cent and 17,788 more than the target of 72,000 which, once again, was presumably the number relevant to which funding was calculated but which was also retained in respect of the assumptions underpinning the 2020-21 Budget.

Worryingly, this increase in presentations reflects demand over only the period from February to June 2020 and so the full-year effect of COVID-19 on demand for mental health services will almost certainly be double this magnitude.

In other words, in relation to just these two categories of the mental health programs there were, in 2019-20, a total of 32,582 more contacts or occasions of service with mental-health clients than anticipated in the targets that underpinned the Budget.

As remarkable as this may seem, what is even more surprising is that in the 2020-21 Budget, prepared with knowledge of the increase in demand for services and delivered at the height of the covid pandemic, the mental health budget suffered an actual cut in funding of $300,000 and the targets set for adults as well as children and youth mental health services are 7 per cent and 20 per cent lower, respectively, than the 2019-20 actual activity levels.

It remains to be seen how many actual mental health contacts or occasions of service there were in the 2020-21 financial year and whether the targets or expectation of mental health case numbers were exceeded to the same degree as they were in 2019-20.

This is obviously, not just because of the alarming data recently reported by “The Weekend Australian” about the experience of young people in Victoria, an issue of fundamental importance.

In addition to the insight which the Canberra data gives us about the mental health of Canberrans, at this most stressful of times, it also raises potentially concerning questions about the capacity of our health services, and especially those dedicated to the care of people with mental-health issues to appropriately meet, including in a timely manner, the needs of their clients.

It would be interesting to know, for example, whether ACT Health has expanded the number of psychiatrists, psychologists and other professionals working in the mental health sphere and whether, for instance, waiting times for people requiring care are within accepted benchmarks.

Jon Stanhope was chief minister from 2001 to 2011 and represented Ginninderra for the Labor Party from 1998. He is the only chief minister to have governed with a majority in the Assembly.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply