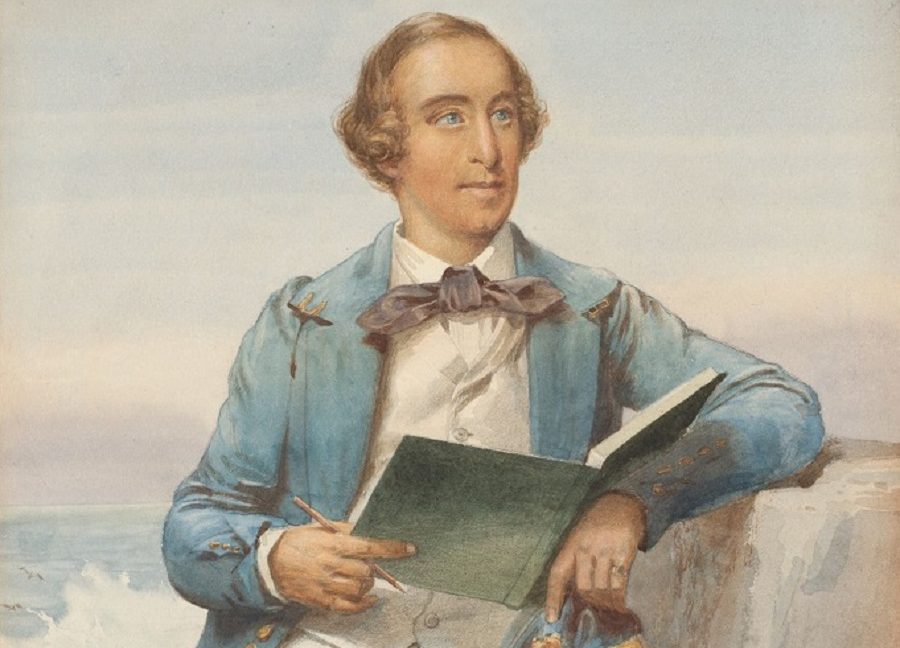

AS it emerges from lockdown, the National Library of Australia has signalled a note of optimism with the opening of an exhibition celebrating both artistry and enterprise, “Illustrating the Antipodes: George French Angas in Australia and New Zealand 1844-1845.”

Co-presented with the SA Museum, the exhibition draws together nearly 200 artworks, sketches and books by English explorer, naturalist and painter, George French Angas, as well as items relating to his life and travels.

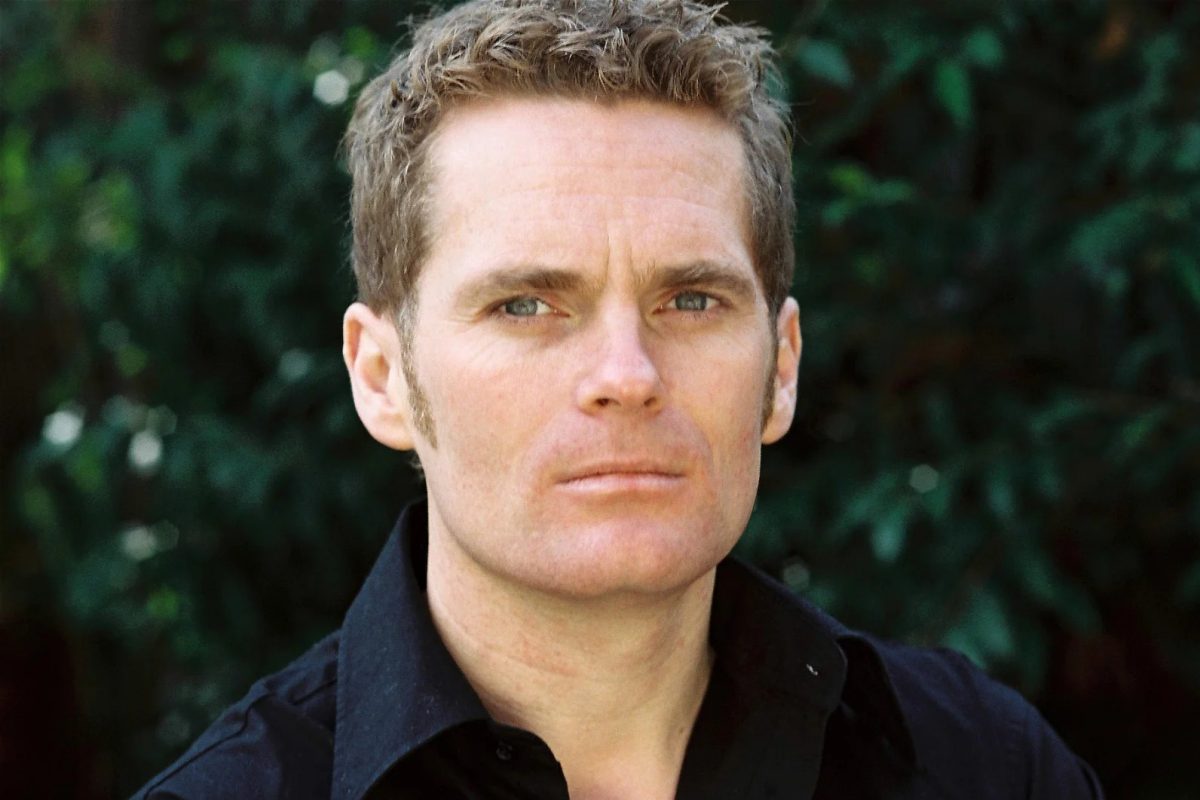

I caught up with the exhibition curator and author of a book on Angas, Philip Jones by phone to Adelaide to talk about his long scholarly fascination with “GFA”, as his subject was often known, the eldest son of George Fife Angas, the businessman and banker who played a significant part in the formation and establishment of SA.

Cut off from Canberra for months by covid, Jones says he hopes to get to see his exhibition in early December.

He has spent much of his working life studying the art and science of the man who first came to SA at age 21, but who was to have an enormous impact on promoting the fledgling colony to the wider world.

By the time he left Australia in 1846, he’d finished several hundred watercolours, including many made on a side trip to NZ, having journeyed to the Murray River lakes, Barossa Valley, Fleurieu Peninsula, the south-east, and later Port Lincoln. They would be exhibited in 1846 at the Egyptian Hall in London.

Born in Newcastle-on-Tyne, but raised in London and Devon, the young George was something of a child prodigy and the NLA exhibition shows a drawing he did on the wall of his bedroom. He had also produced his own magazine at age 16 and circulated it to family members.

Initially self-taught, eventually he took lessons from the premier watercolourists of the era, and from Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins much more famous for the concrete life-size models of dinosaurs displayed in the Crystal Palace.

At just 21, he found himself bound for SA.

GFA’s rich and powerful father George Angas was unable to come to SA until 1851, even though he had helped set it up from afar and had, in the process, inadvertently bought the Barossa Valley.

Instead, he sent his second and more reliable son, John Howard Angas, in 1843, who was followed in 1844 by his older brother George, the latter charged with helping to promote SA as a mercantile venture.

While John Howard Angas succeeded in supervising his land and recovering the family fortunes, GFA had his heart set on being an artist. Despite some family resistance, he mounted the argument that making detailed drawings of SA would help advertise it advantages.

“Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins had turned him from a copyist into someone with a freer hand,” Jones says, “but the detail of his work is exceptional and he was able therefore to fulfil his father‘s brief, which was to produce a public image of SA.”

Jones is at pains to emphasise the idealistic approach of George Angas senior, partly explaining his acquiescence in his older son’s artistic intentions.

A non-conformist Protestant, he wanted freedom of expression and religion, free trade and no hint of convict enslavement in the new SA.

He regarded the German Lutheran immigrants he helped bring out here as almost kindred spirits, analogous to the English dissenters like himself who, until 1883, were not allowed to hold public office or attend university in England.

All this, Jones believes, bottled up the spirit of endeavour and progress in dissenters like Angas, but it found itself an outlet in business.

Non-conformism also nurtured the spirit of giving, and both George Fife and John Howard Angas gave away an enormous amounts of money, helping to set up a traditional of philanthropy in SA, which is often viewed as different from other states.

But GFA’s focus went in other directions and he was, later in life, to achieve fame as a naturalist and an artist.

Happily, the SA Museum, where Jones is a curator, holds a first-rate collection of George French Angas’ watercolours and that, together with his fascinating family background, captured Jones’ interest.

“As I started studying the question of how George French Angas had pulled together his art in just 18 months, I was struck by the contrast between the original watercolours and the lithographs published, but it was a problem to work out in what sequence his imagery of SA life was assembled,” Jones says.

That was because GFA cannily released the pictures episodically in lots of six to stimulate public interest in and sell his many publications, especially “South Australia Illustrated.”

“He was attracted to the art of making records of the landscape and the people, especially the indigenous people, with the ethnographic idea that if not recorded, they might be lost.”

“It’s a noble ideal, but if you don’t have the facility to do it , it’s all talk,” Jones note, but

GFA had a remarkable aptitude for capturing detail, as the works in the exhibition show.

In publishing the results of his travels, which would later take in places as diverse as South Africa, Turkey and Polynesia, GFA engaged three or four lithographers to help interpret the detail of his watercolours and capture his personal style of presenting ethnographic objects and vignettes, but as Jones says, the way he captured the detail in his original sketches meant the lithographers had less work to do.

GFA’s time in Australia was by no means restricted to the 1840s, although the NLA exhibition focuses on that early period.

He married then with his wife and four daughters, came back to Adelaide during the time of the gold rushes, then went to Ballarat and Bathurst, where he made the first public pictures of the goldfields, which were subsequently exhibited at the 1855 Paris exposition.

Ethnography was in fashion and as a documenter of what was going on the lower Murray River, Jones says, Angus‘ name keeps cropping up as a primary reliable source.

In 1853 GFA was appointed to a position at the Australian Museum in Sydney, eventually becoming director and staying a total of seven years, during which time he recorded Sydney’s rock art.

After returning to Angaston, SA, for three years, he returned to England, spending the rest of his life as a specialist in shells.

“It was a remarkable career,” Jones says.

“Illustrating the Antipodes: George French Angas in Australia and New Zealand 1844-1845,” at the National Library of Australia, until January 30.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply