In the first of a three-part critical analysis of the housing market, JON STANHOPE and Dr KHALID AHMED trace how the ACT government’s monopolistic land-release policy deliberately drives up house prices.

A RECENT release from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) reveals that the median price of a house in the ACT increased from $830,000 in the March quarter to $920,000 in the June quarter of 2021 – an increase of $90,000 in three months.

Over the year (June 2020 to June 2021) the increase in median price was a staggering 26.4 per cent. Since that release, market reports indicate further price increases with suburb after suburb breaking through the million-dollar mark.

While the price increase in 2020-21 was particularly large, it continues a trend increase since 2011-12 outstripping income growth.

Apart from a few notable observers who propose supply or demand side solutions, most media commentary falls into two well-established and predictable patterns with:

- Sweeping generalisations, such as that housing (un)affordability is a national problem and that state and territory governments do not have the levers to improve affordability. Some observers take even a broader perspective to paint it as a global problem. Policy solutions then, if any, rest with the federal government. Households need to change their expectations, abandon their unrealistic dreams, and adjust to the “new normal”. Home ownership is not for everyone; or

- Professed fresh insights that the housing market either defies or is not subject to the fundamental law of supply and demand.

We consider the former approach at the very least simplistic and reductionist.

Interestingly, in a recent debate in the Legislative Assembly on a motion by Liberal Mark Parton, for an enquiry into housing unaffordability in the ACT, Housing Minister Yvette Berry resorted to both the above lines of argument, insisting record low interest rates and Commonwealth government tax incentives are the drivers of surging property prices in Canberra.

The motion was, regrettably, amended by the government to require only that the Commonwealth government be lobbied about housing affordability and asked to develop a national housing and homelessness strategy.

For those already owning a house, an increase in family wealth at the rate of a thousand dollars a day provides a sense of increased financial security and an affirmation of the Australian dream.

For those, especially from lower-income households, seeking to buy a house, there is exasperation, feelings of inadequacy, desperation and anger.

While seeking to shift responsibility for the ACT’s severely unaffordable housing, Ms Berry claimed that the government is getting on with the job and providing housing choices to Canberrans. We find this perplexing.

She is also reported as saying that “to suggest that it is just a matter of government supply of land, as a primary cause of house-price increases, ignores everything that has occurred over the last 18 months”, thereby suggesting that the ACT housing market has somehow broken free of the shackles of the law of supply and demand. Incidentally, we are yet to encounter any peer-reviewed research that concludes as such.

The housing choices of Canberrans was revealed in a survey commissioned by the government in 2015, and undertaken by Winton Sustainable Research, in which 91 per cent of households advised that their preferred housing choice was a standalone dwelling. The government’s land-release policy over the last decade reflects the opposite of the findings from that research.

The Minister also recently released a report card on the government’s current housing strategy claiming success in implementing key actions. The strategy warrants a detailed assessment. However, we note that the ACT’s current housing market and affordability outcomes speak for themselves and are an appropriate measure of the effectiveness of the government’s housing strategy.

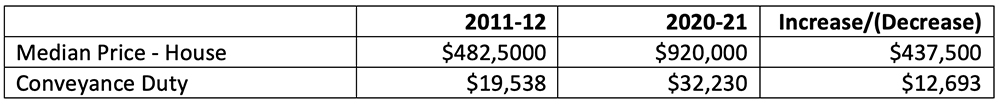

On top of this the Chief Minister and Treasurer regularly promotes the abolition of conveyance duty as the government’s key policy in improving housing affordability. In reality, a household purchasing a median-priced home today will pay more in conveyance duty than was payable 10 years ago when the government embarked on this alleged reform.

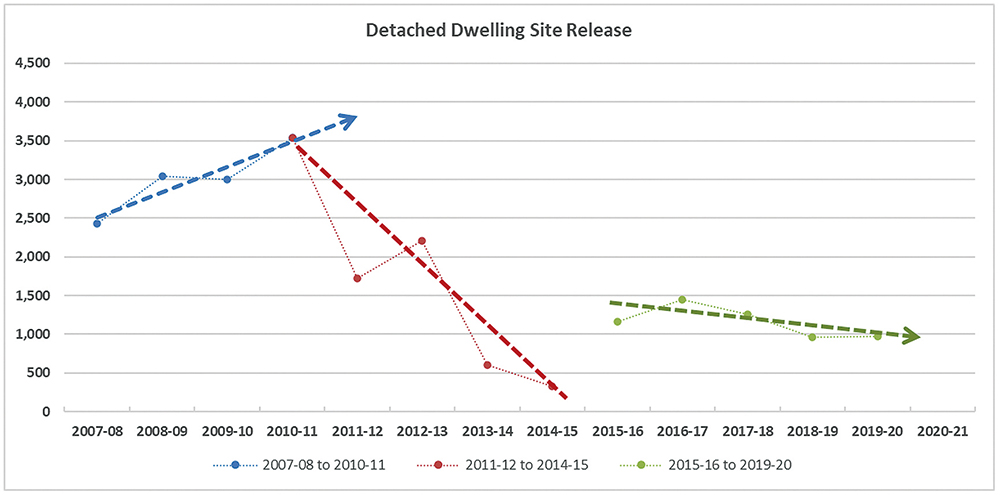

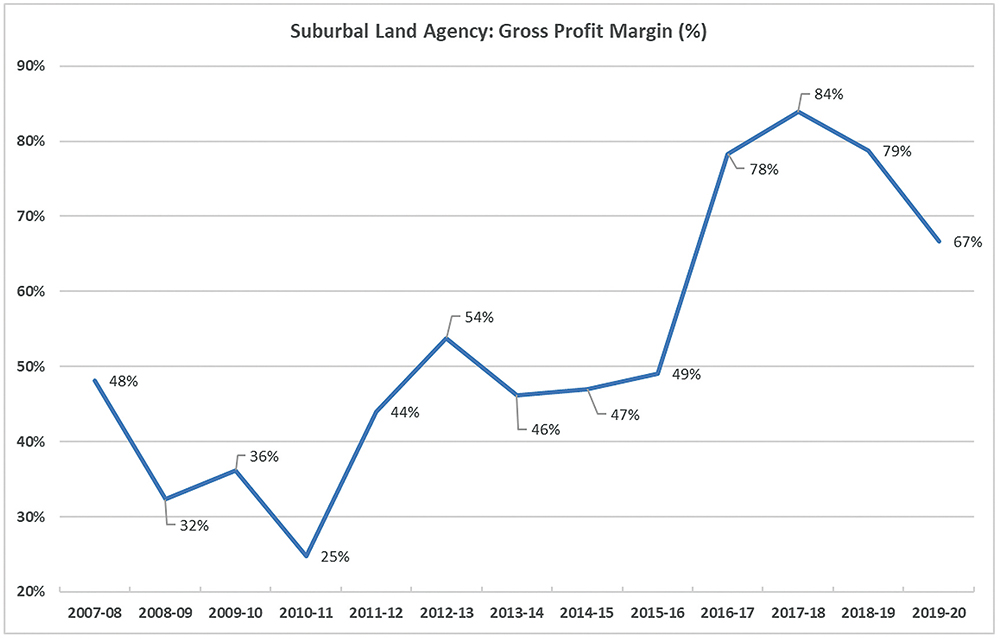

Notably, the charts published here highlight the reverse trend before 2011-12, when the supply increased, profit margin decreased and the median multiple also decreased with a lag of just one year.

The median multiple

The median multiple

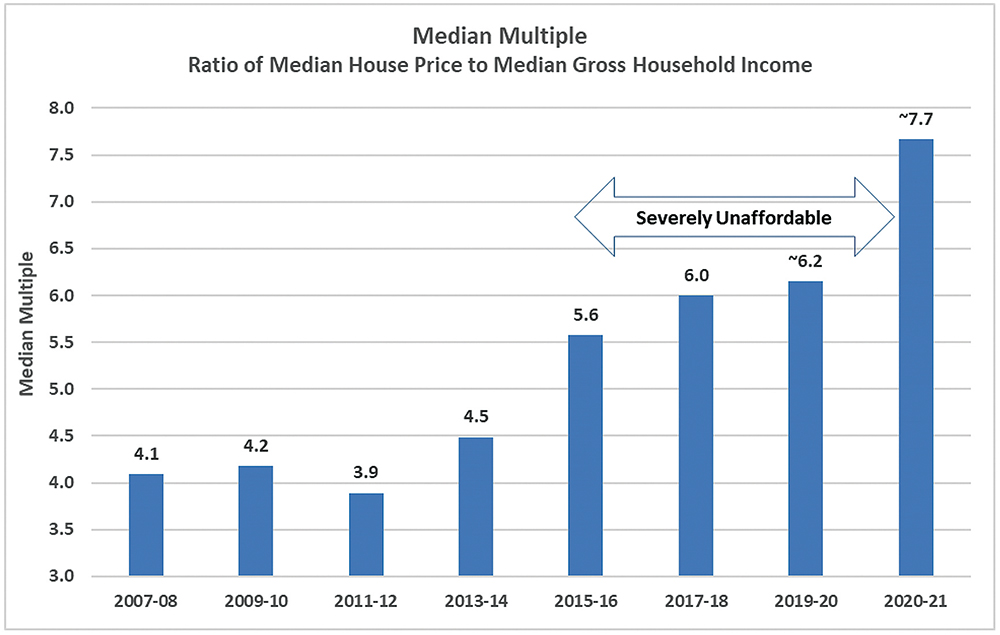

IN 2011-12, a household on median income needed to pay 3.9 times its annual income to purchase a median-priced house. The ratio called “median multiple” is a standard measure of affordability.

In June 2021, the median multiple had increased to around 7.7. A housing market with a median multiple in excess of 5 is considered “severely unaffordable”.

In the ACT, the median multiple has been higher than 5 since 2014-15. Many households seeking to enter home ownership face the initial hurdle of saving enough for an increasingly large deposit, let alone a growing burden of mortgage.

Note: In recent years, the government has not published figures for standalone dwelling sites released. Data from 2017-18 onwards is based on the stated government policy on the percentage share.

Detached dwellings

Detached dwellings

IT is true that state governments in Australia have limited levers to curb price pressures in the housing market. However, the ACT government is an exception – unlike all other states and territories, the ACT has both a single tier of government and hence one planning system, and a total monopoly on the supply of land.

What is occurring in the ACT’s housing market is the culmination of ACT government policies on land supply over almost a decade. Overall land supply for both attached and detached housing decreased from 5048 dwelling sites in 2010-11 to an average of around 3700 sites over the following 10 years, dropping to less than half at 2466 sites in 2011-12. Supply of detached housing sites was particularly constrained, with supply dropping from more than 3500 blocks in 2010-11 to a mere 329 blocks of land in 2014-15.

Profit margins on land

Profit margins on land

During this period, the government’s monopoly supply arm, the then Land Development Agency and now the Suburban Land Agency, posted an abnormal growth in its profits, increasing from $53 million in 2010-11 to $317 million in 2016-17.

Gross profit margin increased from 25 per cent in 2010-11 to 84 per cent in 2017-18. In 2019-20, while activity ceased for part of the year, the gross profit margin was nevertheless 67 per cent (Chart 1).

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply